Economic Stances of Ultranationalist Parties in Western Europe

Posicionamiento económico de los partidos ultranacionalistas en Europa Occidental

Matamoros-Becerra, Javier

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9296-3004

University of Extremadura, Spain

Año | Year: 2024

Volumen | Volume: 12

Número | Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v12i2.814

Recibido | Received: 31-8-2024

Aceptado | Accepted: 4-12-2024

Primera página | First page: 1

Última página | Last page: 24

Los crecientes éxitos electorales de los partidos ultranacionalistas en Europa Occidental han generado un inmenso número de términos para describirlos, siendo derecha radical, extrema derecha y populismo las denominaciones más comunes. Ante este escenario, el objetivo de este trabajo es realizar un análisis sistemático de la ideología de estos partidos en Europa Occidental y compararlos con los existentes en América Latina. Para ello, se ha utilizado la base de datos Chapel Hill Expert Survey para describir los partidos ultranacionalistas en nueve áreas socioeconómicas. El principal resultado hallado es que existe una diferencia notable dependiendo de si estos partidos están situados a un lado, o al otro, del Océano Atlántico. Además, en Europa Occidental, son mucho menos liberales en el ámbito económico que otras familias ideológicas. Especialmente notoria es la posición radical del ultranacionalismo al defender posturas proteccionistas frente al libre comercio mundial. Sin embargo, el aspecto diferencial del ultranacionalismo frente al resto de familias ideológicas es su postulado a favor de políticas de inmigración profundamente restrictivas, siendo además la postura que más consenso genera entre los diferentes partidos aglutinados en esta familia ideológica en Europa Occidental.

Palabras clave: ideología, inmigración, proteccionismo comercio global, ultranacionalismo, Europa Occidental,

The increasing electoral successes of ultranationalist parties in Western Europe have generated an immense number of terms to describe them with radical right, extreme right and populism being the most common denominations. In view of this scenario, the objective of this paper is to carry out a systematic analysis of the ideology of these parties in Western Europe and to compare them with those existing in Latin America. For this purpose, the Chapel Hill Expert Survey database has been used to describe the ultranationalist parties in nine socioeconomic areas. The main result found is that there is a noticeable difference depending on whether these parties are located on one side, or the opposite, of the Atlantic Ocean. Additionally, in Western Europe, they are far less liberal in the economic field than other ideological families. Particularly notorious is the radical position of ultranationalism defending protectionist positions in the face of global free trade. However, the differential aspect of ultranationalism compared to the rest of the ideological families is its postulate in favor of deeply restrictive immigration policies, being also the position that generates more consensus among the different parties united in this ideological family in Western Europe.

Key words: ideology, immigration, protectionism global trade, ultranationalism, Western Europe,

Matamoros- Becerra, J. (2024). Economic Stances of Ultranationalist Parties in Western Europe, methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 12(2), m241202a09. https://doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v12i2.814

1. Introduction

The diverse ultranationalist parties in Western Europe1 have increasingly received electoral support since the 1990s and, particularly, since 2011. Such is the case that more than one fifth of the electorate has chosen to support this type of parties in countries as diverse as Belgium, Finland or France, and has even come to occupy the Presidency of the Council of Ministers of the Italian Republic after the general elections held last September 25, 2022. Also, in Southern European countries (such as Spain, Greece, and Portugal), apparently immune to the rise of ultranationalism, there has been a sudden and surprising increase in support for this type of parties. Thus, in the Portuguese legislative elections of 2024, the ultranationalist Chega obtained 18.10% of the electoral support and Vox entered the regional government of 5 of the 17 Spanish autonomous communities after the last regional elections in 2023.

Additionally, Latin America has experienced some electoral successes of radical right-wing candidates such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and José Antonio Kast in Chile in recent years. This is a quite novel situation since the last decades had been characterized by a concentration of citizen discontent through the radical left in Latin America (Zanotti et al., 2023)Ref40.

Beyond electoral results, in the opportunities in which ultranationalism has reached governmental power, they have generated restrictive policies towards immigration (Acha Ugarte et al., 2020Ref3; Chueri, 2021Ref9; Mudde, 2013Ref26). However, unlike in the 1930s, they have failed to break the liberal democratic framework (Muis & Immerzeel, 2017)Ref28. Additionally, in the United States and Western Europe, their trade isolation has become tangible in the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union and in Donald Trump's restrictive trade policies. This rejection of the globalizing process by ultranationalism is similar to the English Luddism of the 19th century, this time substituting industrial looms for globalization (Rodrik, 2011)Ref32.

These parties have been given different labels such as: populist parties (Gidron & Hall, 2019Ref16; Rooduijn, 2018Ref34); right-wing populist parties (Rama & Cordero, 2018Ref32; van der Waal & de Koster, 2018Ref39); radical right (Kriesi & Schulte-Cloos, 2020Ref21; Lancaster, 2019Ref22); radical right populist parties (Evans & Ivaldi, 2020Ref13; Mazzoleni & Ivaldi, 2020Ref24); extreme right (Allen & Goodman, 2021Ref4; Halikiopoulou & Vlandas, 2016Ref18) or, simply, anti-immigration parties (Abbondanza & Bailo, 2018)Ref1.

Given this sociopolitical context, the main objective of this investigation is to describe the socioeconomic ideological framework that forms part of the ultranationalist parties in Western Europe after a systematic analysis in order to be able to define their identity pattern. Additionally, a comparison is made between the existing ultranationalist parties in Western Europe and the Latin American radical right. The justification for the simile with Latin America is motivated by the tendency of studies in this field to focus on Western Europe, ignoring Latin American trends (Zanotti et al., 2023)Ref40.

Next, in the theoretical framework, we proceed to describe the current situation in Western Europe, the socioeconomic particularities existing in Latin America and previous denominations that have been attributed to this type of political parties. Subsequently, the methodology carried out is described and, in the fourth section, the different results found are presented. Finally, the fifth section concludes the paper.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Current situation

In order to analyze the current situation of ultranationalism in Western Europe, the results of the last elections to the European Parliament (held in June 2024) have been taken as a reference. These elections have been chosen as they were held simultaneously in all the member states of the European Union (making easier comparison), they represent a long time series of data, and they favor the real representation of support for the different political parties as European Parliament elections are characterized by low entry thresholds (Halikiopoulou & Vlandas, 2016Ref18; Nicoli & Reinl, 2020[ref29]).

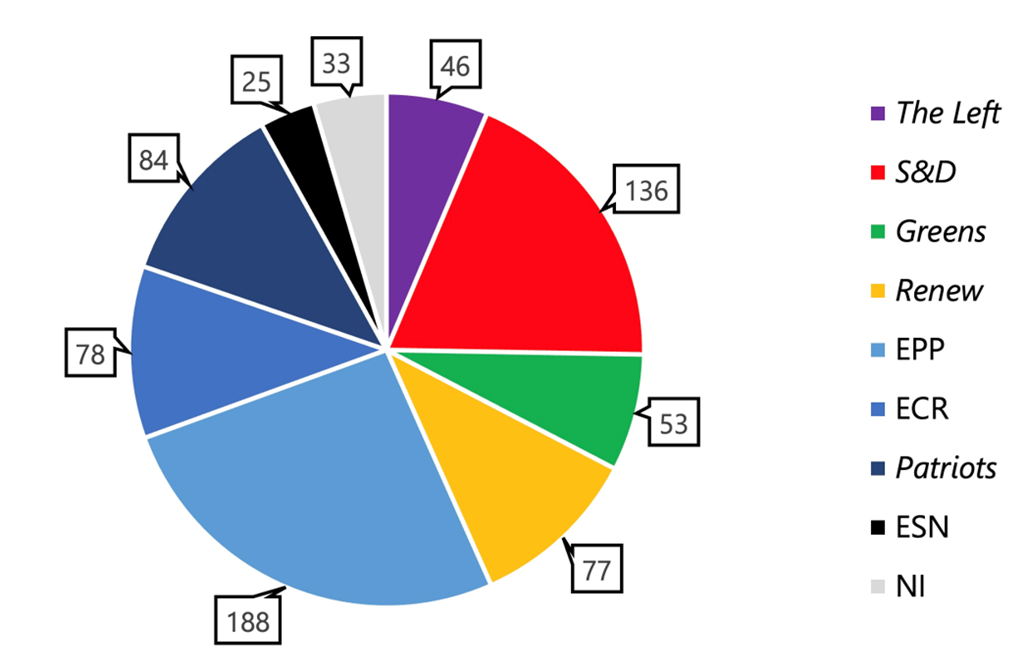

As a result of these elections, the ultranationalist parliamentary group Patriots for Europe emerged as the third political force with the largest number of members (84) after the historical European People's Party Group (188) and Socialist and Democrats Group (136). In fact, ultranationalism was the most voted electoral option in four Western European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, and Italy). Additionally, these elections have definitely brought the end of the Iberian exception (Alonso & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2015)Ref5.

Spanish ultranationalism entered the European Parliament for the first time after the elections held in 2019, and in 2024 it has seen its position strengthened with an electoral increase. For its part, Portuguese ultranationalism (represented by the political party Chega2) has also entered the European Parliament with a support of 9.99% as can be seen in Figure 1. Nevertheless, ultranationalism achieves lower support in Southern Europe compared to Central Europe, with the exception of Italy. In fact, the Council of Ministers of this country is led by Giorgia Meloni (secretary general of the ultranationalist Fratelli d'Italia) and vice-chaired by Matteo Salvini (leader of the ultranationalist party Lega). Italy was the country where ultranationalism achieved the highest support in the last elections to the European Parliament (37.74%).

In Southern Europe –specifically in Spain, Greece and Portugal– there are a set of common characteristics that hinder the success of ultranationalism: recent presence of extreme right-wing dictatorships, strong parties of the Christian Democratic ideological family, absence of a developed Welfare State after World War II, entry into the European Union during the 1980s, being net recipients of European aid until the extension of the European Union to Eastern Europe, and a strong impact of the Great Recession (Ellinas, 2013Ref11; Halikiopoulou & Vasilopoulou, 2018Ref17).

In addition to these three countries, ultranationalism received little electoral support in Ireland and Luxembourg in the last elections to the European Parliament. So little support was received by ultranationalism in these countries that it did not even obtain a Member of the European Parliament (MEP, henceforth). In the case of Ireland, the division of the country into electoral districts makes it difficult for new political parties to join the already established ones. The country is divided into three constituencies to barely distribute 14 MEPs. On the other hand, the small number of MEPs to be distributed in the case of Luxembourg (just six) also hinders the entry of new electoral contenders. However, in this case, a party such as Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei [Alternative Democratic Reform Party] is observable there with an electoral support of 11.77% in the last European elections. Although this party shares a parliamentary group with openly ultranationalist political parties, such as Fratelli d'Italia, it differs from this ideological family in aspects such as migration policy or the position on the European Union (Jolly et al., 2022)Ref19.

Together with the previously mentioned countries, in which ultranationalism was the option with the greatest support (Austria, Belgium, France, and Italy), the result achieved in the Netherlands (16.97%) and Germany (15.09%) should be underlined. In the first of these cases, this result only strengthened the electoral result of Partij voor de Vrijheid in the general elections of 2023, in which it was the electoral option with the greatest support.

As can be seen from Figure 2, ultranationalism has advanced across Western Europe comparing to 2019. There are only three exceptions: Finland, Sweden, and Italy (ordered by level of decline in electoral support for ultranationalist parties). In the case of Italy, even though ultranationalism is the most voted political option, and where it has the highest support in all Western Europe, the sum of the Fratelli d'Italia and Lega in 2024 is lower than in 2019.

In addition to Italy, it is worth mentioning several countries where a couple of ultranationalist parties coexist with representation in the European Parliament: Denmark, France and Greece. Another consequence of the elections to the European Parliament has been the generation of three ultranationalist Euro parliamentary groups as opposed to the two existing in the 2019-2024 legislature (Identity and Democracy, and European Conservatives and Reformist Group). In addition to the aforementioned Patriots for Europe group, the 10th legislature in the European Parliament once again has European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) and, additionally, European of Sovereign Nations (ESN) group, as shown in Graph 13.

The group Patriots for Europe includes the main ultranationalist referents such as: Chega (Portugal), Dansk Folkeparti (Denmark), Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (Austria), Lega (Italy), Partij voor de Vrijheid (Netherlands), Rassemblement National (France), or Vlaams Belang (Belgium). A second ultranationalist Euro parliamentary group is constituted by ECR. This group is the fourth with the largest representation (78) ahead of two historical groups in the Europarliament such as the liberal group Renew Europe (53) and the Greens (53). In this parliamentary group, openly ultranationalist political forces (such as Fratelli d'Italia, in Italy; Perussuomalaiset, in Finland; or Sverigedemokraterna, in Sweden) coexist with other rather more moderate political parties (such as Niew-Vlaamse Alliantie [New Flemish Alliance], in Belgium; or Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei, in Luxembourg).

A third ultranationalist group in the European Parliament is the so-called Europe of Sovereign Nations. This parliamentary group is made up of only two parties in Western Europe: Alternative für Deutschland (Germany) and Reconquête (France). The origin of this group comes from journalistic reports linking leaders of Alternative für Deutschland to neo-Nazism, which led to its expulsion from the European group Identity and Democracy.

In addition to Western Europe, the ultranationalist movement is gaining strong support in other latitudes. For example, the United States has witnessed the rise of the nativist and isolationist candidacy of Donald Trump (Gest et al., 2018)Ref15. Also in Latin America, there is an increase in support for different radical right-wing parties with the most patent examples being Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and José Antonio Kas in Chile. This is quite a novel event in this region since the 1990s and the beginning of the 21st century was characterized by the channeling of citizen discontent through the radical left (Rodrik, 2018Ref33; Ubilluz Raygada, 2021Ref37; Zanotti et al., 2023Ref40).

Latin American radical right-wing parties are allied with European ultranationalism through the Madrid Charter4. This attempt to generate an Ibero American space was not only joined by leaders of Vox and Chega, but also by leaders of different French, Greek, Italian and Swedish ultranationalist parties.

2.2 Socioeconomic particularities in Latin America

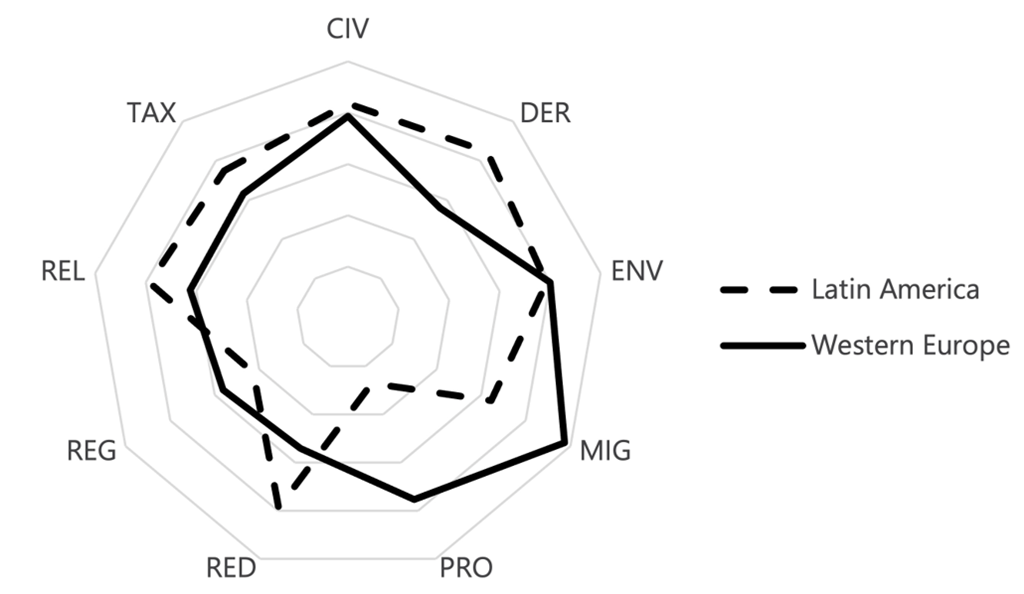

Although radical right-wing parties are beginning to appear in Latin America, as has been the case in Western Europe for decades, the two regions have quite different characteristics. Looking atRef38 Graph 25, Western European countries are characterized by a higher percentage of immigrant population than Latin American countries. The only Latin American countries with significant immigration are Costa Rica (10.22%), Chile (8.61%) and Panama (7.26%).

Likewise, the data on socioeconomic inequality are quite different from one side to the other. According toRef36 Graph 36, all Latin American countries show higher inequality than in Western Europe. Inequality is especially high in Colombia (0.55), Brazil (0.52) and Panama (0.49). Even the country with the lowest level of equity in Western Europe (Italy) is more equal than the state with the lowest inequality in Latin America (Dominican Republic).

This different pattern in the socioeconomic characteristics of the two regions has made possible the success of the radical left in a considerable number of countries in Latin America, and of ultranationalism in Western Europe, according to several authors. In Latin America, the presence of high inequality together with the small number of immigrants has historically prevented ultranationalist parties from performing well (Zanotti et al., 2023)Ref40. On the contrary, this scenario has benefited radical left parties focused on income redistribution (Rodrik, 2018)Ref33. For its part, the feature of globalization that has been most prominent in Western Europe has not been socioeconomic inequality but immigration. This fact has given rise to ultranationalist parties in this area by being especially restrictive with immigration (Rodrik, 2018)Ref33.

2.3 Background

After World War II, a first wave of ultranationalist parties (of which the Movimiento Sociale Italiano [Italian Social Movement], MSI, stood out) was characterized by a neo-fascist ideology. According to Graph 4Ref7, even the most relevant party of this first wave had little electoral success. In the 1980s, a second wave appeared in which the “winning formula” was a conservative essence in the social sphere, xenophobia, and liberal stances in the economic field (Acha Ugarte, 2021Ref2; Kitschelt & McGann, 1995Ref20). Some of the most successful ultranationalist parties of this stage are still successful today, but they have significantly changed their positions. Several examples are Rassemblement National (in France) or Vlaams Belang as the successor party of Vlaams Blok [Flemish Block] (in Belgium).

Currently, these parties are given a wide variety of terms: populist, radical right, extreme right and so on. Although the term populism has become a terminology in vogue, its scarce concreteness makes its use impossible. According to Mudde & Rovira (2019)Ref27, populism requires a strong ideology in which to anchor itself such as nationalism, liberalism, or socialism. This is why populism does not say much. In fact, European political parties as diverse as La France Insoumise [Unbowed France] (France), Die Linke [The Left] (Germany), SYRIZA (Greece), Sinn Féin [We Ourselves] (Ireland), Forza Italia [Forward Italy]or Movimento 5 Stelle [Five Star Movement](Italy) are described as populist (Rooduijn et al., 2023)Ref35.

Certainly, what seems quite clear is that this type of political parties in Western Europe are distancing themselves from neo-fascist or neo-Nazi positions either by ideological principles or by a desire to maximize their electoral options. A clear example of this strategic shift has been the programmatic turn of the French Front National after the arrival of Marine le Pen to the party leadership in 2011 (Ubilluz Raygada, 2021)Ref37. Another example of separation with neo-Nazism has been the rupture of relations of a large part of European ultranationalism with the German Alternative für Deutschland party after the controversial statements of one of its candidates to the European Parliament about the Nazi paramilitary organization SS (Bassets & Verdú, 2024)Ref6.

Based on the central objective of the analysis, two hypotheses have been established in the study. The first of these assumes that, since most of the ultranationalist parties are integrated into one electoral group in the European Parliament, their ideological stance is homogeneous. Therefore, the first hypothesis is defined as follows:

H1: There is an ideological similarity in socioeconomic stance among the existing ultranationalist parties in Western Europe.

In addition, the diverse socioeconomic particularities existing in Latin America compared to the context in Western Europe make it possible for the ideological positioning of European ultranationalism to be different from the new radical right-wing parties originated in Latin America. Therefore, the second hypothesis of the study is described as follows:

H2: There are considerable ideological differences in socioeconomic aspects between the ultranationalist parties in Western Europe and the radical right in Latin America.

3. Methodology

In order to meet the stated objective, information provided by the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (hereinafter referred to as CHES) database has been used. This database collects the ideological stance on various issues of political parties in Europe and Latin America. Specifically, it includes information on 277 European and 112 Latin American political parties (Jolly et al., 2022)Ref19. The first edition on European political parties dates from 1999 and the sixth edition, the latest at the time of writing this paper, corresponds to 2019. The latter edition was used to carry out the research presented. In relation to Latin America the only available database has been used, which dates from 2020 (Martínez-Gallardo et al., 2022)Ref23.

The work has focused on Western Europe because of the eminent differences with Eastern Europe generated by the communist legacy in social, cultural, and economic fields (Brils et al., 2020Ref7; Dennison & Geddes, 2019Ref10; Finnsdottir, 2019Ref14). Specifically, it has been taken as reference the countries belonging to the former EU-15 where the ultranationalist party (or ultranationalist parties) of reference got at least one MEP in the last elections to the European Parliament (June 2024) and was integrated in some of the parliamentary groups in the constitution of the Parliament. Of these fifteen countries forming the EU-15, Ireland and Luxembourg have been left out of the study. In the case of these two countries, ultranationalism was not able to obtain a deputy in the last European elections.

The Portuguese case has not been considered either, since although the ultranationalist political party of reference (Chega) achieved an important entry in the European Parliament, it had not been qualified by CHES in the latest existing version at the time of writing this paper (2019). Likewise, a few political parties have also not been considered, although they achieved parliamentary representation, as they were not coded in the latest edition of CHES for their recent creation: Danmarksdemokraterne (Denmark), Reconquête (France), and Foni Logikis (Greece). In these three cases, there is another ultranationalist party of reference in each country coded by CHES. Table 1 shows the ultranationalist parties included in the analysis. In Italy there are two reference ultranationalist parties with parliamentary representation. Therefore, the sample size is twelve ultranationalist political parties.

The aforementioned variables have been chosen since of the 27 variables collected by CHES in its European version, only 15 are also measured in Latin America. Some of these variables, such as position on the European Union or Russian interference, are understandably absent in the case of Latin American political parties due to their markedly European characteristics. Other variables, such as ideology or general economic stance, have also been discarded because of their enormous vagueness.

A further step has been to compare the stance of European ultranationalism with the rest of the ideological families in Western Europe. Table A2 shows the referents of these political families in each country. In order to determine whether a political party belongs to a certain group, the following requirements must be fulfilled:

(1) The political party under consideration must have won at least one MEP in the last elections to the European Parliament (June 2024); (2) It must be registered in a European parliamentary group on the date of constitution of the tenth legislature of the European Parliament (July 2024). (3) A third requirement is that the party has been previously coded in the latest available version of CHES. Most political parties meet this requirement. (4) A final requirement is that the political party is located in a country with at least one ultranationalist party of reference. Therefore, political parties located in Ireland and Luxembourg are discarded.

Given the recent performance of radical right parties in Latin America, a next step has been to analyze the Latin American political parties that are signed up to the Madrid Charter and are collected by the Latin American version of CHES (Martínez-Gallardo et al., 2022)Ref23. However, a limitation of this database is that does not cover Central America (with the exception of Costa Rica). Additionally, despite the interest awakened by the figure of Javier Milei after his victory in the Argentine presidential elections held on November 19, 2023, it is not possible to include him in the analysis because the last available version (and only one, so far) of CHES in Latin America dates from 2020 and the political party that covers his figure (La Libertad Avanza) had a later emergence.

Table 3 shows the political parties that meet the two selected requirements. In the case of Chile, the ideological position of the Unión Demócrata Independiente has been analyzed, since Partido Republicano is a split of this party and was not analyzed by CHES in 2020. In the cases of Costa Rica and Ecuador, the signatory political parties (Costa Rica Justa and Libertad es Pueblo, respectively) were not included in the latest version of CHES available at the time. In the cases of Paraguay and Uruguay, no political parties (but individual personalities) are among the signatories. In the case of Venezuela, the signatory is a conglomerate (Frente Amplio Venezuela Libre) of political parties whose only connection is the opposition to Maduro.

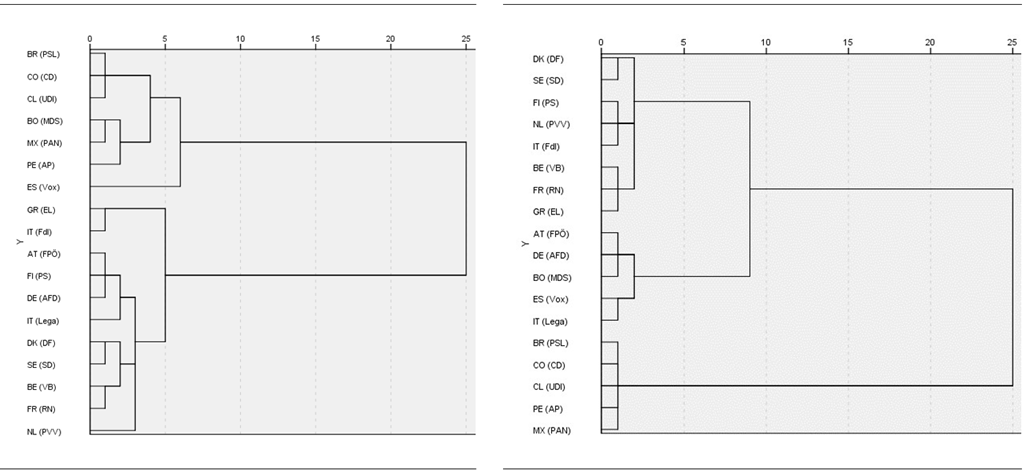

Finally, two dendrograms were constructed to determine possible subcategories of parties beyond geographical differences. Ward's method has been applied for the elaboration of these graphs.

4. Results

As shown in Graph 5, the ultranationalist parties in Western Europe have a radical position on immigration and environmental policy. Their position is strongly restrictive on immigration, and they are inclined to support economic growth measures even though they may have environmental damage as a counterpart. In addition, these are the two variables in the whole model with the greatest consensus. Table A3 shows the ideological positioning of all the political parties included in the analysis in numerical terms (0-10), separated by ideological families and showing the mean position, standard deviation, maximum value and minimum value for each of the variables analyzed.

In terms of economic stances, with the exception of the variable protectionism, moderate positions are observed, although with large oscillations depending on the political party. Thus, in the same ideological family coexist parties with a liberal economic ideology –in favor of market deregulation, against income redistribution, and in favor of low taxes– such as Vox or Lega with parties with antagonistic positions such as Elliniki Lisi or Dansk Folkeparti. As for economic protectionism, there is a greater homogeneity of economic postulates against global free trade.

Continuing with the variables of the social field, an eminent conservative position is also palpable, although with a greater heterogeneity than in the case of immigration and environmental policy. Thus, for example, conservative ultranationalist parties such as Elliniki Lisi or Vox, coexist with other ultranationalist political parties with a moderate vision such as Partij voor de Vrijheid or Dansk Folkeparti. Some European ultranationalist parties, such as the French Rassemblement National, have chosen to formally accept same-gender marriage as an ideological weapon against allegedly sexist and homophobic Muslim immigrants (Ubilluz Raygada, 2021)Ref37.

Among all the variables analyzed, those with the greatest heterogeneity are political decentralization and religious principles. As for the positions on political decentralization, the highly contrary stance promoted by Vox stands out with the favorable positions promoted by the Belgian Vlaams Belang and the Italian Lega. It should not be forgotten that both Vlaams Belang and Lega defend greater autonomy for a part of the state territory (the region of Flanders and the fictitious Padania, respectively), and Vox has experienced a quick political growth as a reaction to the pro-independence attempt carried out in Catalonia in 2017. There is even greater heterogeneity among the different postulates on the role that religious principles should play in politics.

Once the stance of ultranationalism in Western Europe has been analyzed, the positions of these parties are compared with the European ideological families of moderate right, liberal, social democratic, radical left, and green parties in the European Parliament after the elections of June 2024.

As Graph 6 shows, in the economic dimensions (market deregulation, income taxation and tax policy) moderate right-wing and liberal parties postulate a more liberal ideology than ultranationalist forces. However, in terms of protectionist postulates, ultranationalism holds the most extremist position against global free trade, with the radical left parties following behind. In contrast, liberal and moderate right-wing parties are openly in favor of global trade.

Once again, it can be seen that immigration policy is the differentiating and specific issue of ultranationalism, since it is in this variable that there is the greatest difference with the following ideological family (moderate right-wing parties). Despite the heterogeneity of positions of the different ultranationalist political parties on civil rights, their average position continues to be manifestly more conservative than that expressed by the moderate right and antagonistic to the rest of the political families.

Likewise, the stances of Western European ultranationalism on environmental policy are the most extreme in the European political landscape. It is the European political family that is most prominently positioned in favor of economic activity even though it could go against environmental sustainability. For its part, the position on the presence of religion in political life is practically identical to that held by the moderate right-wing parties. Finally, the position on political decentralization is the one with the fewest differences among the political families. Not coincidentally, it is the variable with the greatest heterogeneity of ideological approaches in each European political family.

Among the radical right-wing parties in Latin America, Graph 7 shows that they are highly supportive of ultraliberal positions in the economic field. In particular, they are in favor of market deregulation, against income redistribution and in favor of tax reductions. These variables are the most homogeneous within this ideological family in Latin America. They also show a radical position in favor of global free trade and against protectionist measures.

Other radical positions held by the radical right in Latin America are those related to civil rights and environmental policy. Regarding these issues, these parties are very conservative and prioritize economic activity over environment activity. In terms of immigration policy, there is a considerable variation from country to country. For example, the restrictive position towards immigration held by the Chilean political party Unión Democrática Independiente stands out. It makes sense that in Latin America the migratory issue is not given special importance, since the percentage of immigrants is low, at least in relation to Western Europe. In fact, Chile is the third country in the region (after Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic) with the highest percentage of immigrants, largely due to the flow of immigration from Venezuela since the first half of the 2010s. Regarding the role that religion should play in the political arena and the regionalist issue, the heterogeneity of positions put forward by these parties makes it impossible to establish a common position.

Comparing the positions of ultranationalism in Western Europe with the radical right in Latin America, it can be seen in Graph 8 that there are strong differences in terms of immigration policy and economic issues. While in Western Europe it has been noted that the ultranationalist parties are very restrictive on immigration, this is not the case of the Latin American radical right. However, the most notable difference between the two political families is their stance on protectionism. While in Latin America the defense of global free trade is a priority, European ultranationalism postulates protectionist measures to supposedly protect the domestic enterprises. Likewise, the discrepancies in the rest of the economic perspectives are notorious. The radical right in Latin America is eminently liberal in this area, unlike European ultranationalism.

Regarding positions on religion and regionalism, the radical right in Latin America is in favor of political decentralization, as opposed to what is postulated by European ultranationalism. In addition, it is more in favor of religion having a relevant role in political life. The positions on civil rights and the environment are analogous.

Figure 3 shows the result of the dendrogram applied to the existing set of ultranationalist parties in Western Europe and Latin American radical right-wing parties. First of all, it should be noted that geographical differences matter. On the one hand, all the Western European ultranationalist parties are grouped together. However, there is one exception: Vox. This political party is more similar to the Latin American radical right than to its European partners in economic matters in areas such as deregulation of markets, opposition to income redistribution and, to a lesser extent, favoring tax reductions. However, in relation to global free trade, Vox's position is closer to that of its European partners. These ideological similarities have probably encouraged Vox to generate a common front together with the Latin American radical right and tangible through the Madrid Forum.

Figure 4 again shows the different stances of ultranationalist and radical right-wing political parties in both regions, but this time considering only the economic varieties. The set of parties analyzed is differentiated into three clear groups. The first group includes most of the ultranationalist parties in Western Europe. In the second group are the rest of the ultranationalist parties not included in the first group (Alternative für Deutschland, Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, Lega, and Vox), and the Bolivian party Movimiento Demócrata Social. This group is characterized by liberal positions on market deregulation, income redistribution and tax policy. However, the position of these parties on protectionist measures in the context of global free trade is quite moderate. Finally, a third group is composed of the rest of the Latin American parties analyzed. This group is characterized by promoting ultraliberal positions including the promotion of global free trade.

Despite the recent exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union, the socioeconomic positioning of ultranationalism in that country is also shown. Following the work of Brils et al. (2020)Ref8, Halikiopoulou & Vlandas (2016)Ref18, Kriesi & Schulte-Cloos (2020)Ref21, and Rama & Cordero (2018)Ref31, United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) has been taken as the reference ultranationalist political party in the United Kingdom. The ideological position of this party has been compared with that of the main political parties in the United Kingdom in Graph 9 and with that of the existing ultranationalism in Western Europe and the radical right in Latin America in Graph 10.

In order to be able to compare ultranationalism in the United Kingdom with the rest of the ideological families, the political parties of Great Britain with representation in the European Parliament after the elections of May 2019 (the last in which the United Kingdom participated as a Member State of the European Union) have been taken into consideration. In Table 4Ref12, we proceed to indicate the political parties with Euro parliamentary representation after the 2019 elections, their acronyms and the ideological family in which they belong by virtue of the group to which they belonged during the IX legislature of the European Parliament.

Graph 9 shows that the main divergence of ultranationalism with respect to the rest of the parties in the United Kingdom is its policy on civil rights, as it is much more conservative than the Conservative Party. On the other hand, positions close to the Conservative Party can be seen in the economic variables of market deregulation, income redistribution and tax policy. In relation to protectionism, the Labour Party is the party that most rejects free trade, followed by the Green Party.

Comparing UKIP's position with the rest of the ultranationalist parties in Western Europe, and with the radical right in Latin America, there is a great similarity in the conservative position on civil rights and the environmental policy. However, UKIP's liberal position on economics (visible in variables such as deregulation of markets and positioning on income redistribution) is more like the Latin American radical right than to European ultranationalism. In contrast, the restrictive ideology towards immigration makes UKIP much more similar to European ultranationalism.

The results found are in line with previous research that considers immigration to be the star topic of ultranationalism, considering it a threat for cultural and economic reasons (Acha Ugarte et al., 2020)Ref3. The work of Olmos Alcaraz (2023)Ref30 also reached this conclusion by analyzing the messages of Spanish ultranationalism during the regional electoral campaign in Andalusia in 2022. However, in the field of civil rights, there are such differences between the different parties that it is not feasible to affirm that these ultranationalist parties are univocally conservative. Likewise, in economic matters, ultranationalism in Western Europe has changed its characteristic positions in the 1980s, moving from ultraliberal positions to an ideological moderation in this issue. These ideological lines differentiate these parties from the Latin American radical right. The latter is characterized by a socially conservative agenda, opposed to feminist and LGTBI demands, and neoliberal in the economic arena (Morán Faúndes, 2023Ref25; Ubilluz Raygada, 2021Ref37). Additionally, the Latin American radical right does not present itself particularly restrictive with respect to immigration.

With the results found in the analysis it is not possible to accept the H1 of the paper. While it is true that there is a great similarity in the restrictive position towards immigration and (to a lesser extent) in environmental policy, a great divergence of postulates has been found in other matters. Thus, the ultranationalist parties have a wide range of ideological positions on civil rights and economic issues. However, the greatest economic differences are to be found in the role that religion should play in politics and regional policy. For all these reasons, H1 must be rejected and it must be stated that there are deep ideological differences between the various ultranationalist parties in Western Europe despite the fact that most of them are grouped together in the same political group in the European Parliament.

As for H2, there are such programmatic differences between the parties analyzed in Western Europe and those considered in Latin America as to affirm that they are notoriously different. The ultranationalist parties in Western Europe are much more restrictive towards immigration than in Latin America. Likewise, the radical right in Latin America is ultraliberal in economic matters compared to the divergence of postulates found among the ultranationalist parties present in Western Europe. The main difference is found in the protectionism variable. While in Western Europe these parties are in favor of protectionist measures in the face of global free trade, they hold the opposite position in Latin America. These substantial differences, depending on whether they are on one side of the Atlantic Ocean or the other, make it impossible to use a single terminology to refer to them in a broad sense.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Given the sudden electoral rise of ultranationalist parties in Western Europe, and the radical right in Latin America, a series of terms have been coined to describe them: radical right, extreme right, populists... For this reason, this investigation has set the objective of carrying out a systematic analysis capable of providing a detailed understanding of the identifying characteristics of these ideological families.

One of the most commonly term used is populism. However, this label is extremely vague as it requires a strong ideology in which to be hosted and does not say much by itself. Likewise, the extreme right is characterized by a desire to subvert the democratic system, which is a characteristic that this type of party, at least in Western Europe, lacks. Likewise, the term radical right was a valid terminology in the second wave of these parties after World War II. The parties that emerged at this stage were characterized by being extremely conservative in the social field, ultraliberal in the economic arena, and anti-immigration.

However, at current, ultranationalist parties in Western Europe are less liberal on economic issues than the liberal and moderate right-wing parties. In addition, in terms of economic protectionism, they maintain an antagonistic position to these two families. In relation to the view on civil rights, European ultranationalism has a great heterogeneity of positions within it. As a result, the “winning formula” characteristic of the 1980s has been broken. Not surprisingly, some ultranationalist parties from that decade have considerably changed their ideological line. In the issue in which they maintain a differential postulate, and with great consensus, is the rejection of immigration.

In view of this discursive change, throughout this paper it has been always chosen to use the term ultranationalist parties, rather than the radical right, in view of the preponderance of the nation-state promulgated by these parties in the face of any exogenous element. Exogenous elements received either through global trade or through global migrations considered as an economic and cultural threat.

Moving on to analyze the radical right in Latin America –and comparing it with the ideology of ultranationalism in Western Europe –, it can be observed that it maintains ultraliberal positions in the economic field. The main difference is that while the Latin American radical right is particularly liberal in the case of global free trade, ultranationalism in Western Europe is notoriously protectionist. By additionally maintaining conservative positions in the social sphere, the analyzed parties in Latin America could be labeled as radical right (as has been done throughout this paper) for complying with the “winning formula”. However, in Latin America, these parties are not particularly opposed to immigration. This is logical, since immigration is not the dimension of globalization that has had the greatest transcendence in Latin America.

Finally, the dendrogram shows that the differences between these parties are evident depending on whether they are on one side or the other of the Atlantic Ocean. However, the particularities of the Spanish ultranationalist political party, Vox, make this party more similar to Latin American parties than to their European counterparts. As a limitation of the paper, the data used are based on the latest version of the CHES database with information from the years 2019, for Western Europe, and 2020, for Latin America.

Annexes

1) Abbondanza, G., & Bailo, F. (2018). The electoral payoff of immigration flows for anti-immigration parties: the case of Italy’s Lega Nord. European Political Science, 17(3), 378-403. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-016-0097-0

2) Acha Ugarte, B. (2021). Analizar el auge de la ultraderecha. Editorial Gedisa.

3) Acha Ugarte, B., Innerarity Grau, C., & Lasanta Palacios, M. (2020). La influencia política de la derecha radical: Vox y los partidos navarros. methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 8(2), 242- 257. https://doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v8i2.384

4) Allen, T. J., & Goodman, S. W. (2021). Individual-and party-level determinants of far-right support among women in Western Europe. European Political Science Review, 13(2), 135- 150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000405

5) Alonso, S., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2015). Spain: No Country for the Populist Radical Right? South European Society and Politics, 20(1), 21-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.985448

6) Bassets, M., & Verdú, D. (2024, May 21). Le Pen y Salvini rompen con la AfD alemana tras las declaraciones de un candidato sobre las SS. El País. https://bit.ly/3y6Zgn2

7) Berlinguer, E. (1977). La cuestión comunista. Editorial fontanera.

8) Brils, T., Muis, J., & Gaidyte, T. (2020). Dissecting Electoral Support for the Far Right: A Comparison between Mature and Post- Communist European Democracies. Government and Opposition, 57(1), 56- 83. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.17

9) Chueri, J. (2021). Social policy outcomes of government participation by radical right parties. Party Politics, 27(6), 1092-1104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820923496

10) Dennison, J., & Geddes, A. (2019). A rising tide? The salience of immigration and the rise of anti-immigration political parties in Western Europe. Political Quarterly, 90(1), 07-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12620

11) Ellinas, A. A. (2013). The Rise of Golden Dawn: The New Face of the Far Right in Greece. South European Society and Politics, 18(4), 543-565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2013.782838

12) European Parliament. (n.d.). European Parliamen 2024- 2029. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://results.elections.europa.eu/en

13) Evans, J., & Ivaldi, G. (2020). Contextual Effects of Immigrant Presence on Populist Radical Right Support: Testing the “Halo Effect” on Front National Voting in France. Comparative Political Studies, 54(5), 823-854.https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020957677

14) Finnsdottir, M. S. (2019). The Costs of Austerity: Labor Emigration and the Rise of Radical Right Politics in Central and Eastern Europe. Frontiers in Sociology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00069

15) Gest, J., Reny, T., & Mayer, J. (2018). Roots of the Radical Right: Nostalgic Deprivation in the United States and Britain. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1694- 1719. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017720705

16) Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2019). Populism as a Problem of Social Integration. Comparative Political Studies, 53(7), 1027-1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019879947

17) Halikiopoulou, D., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2018). Breaching the Social Contract: Crises of Democratic Representation and Patterns of Extreme Right Party Support. Government and Opposition, 53(1), 26- 50. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2015.43

18) Halikiopoulou, D., & Vlandas, T. (2016). Risks, Costs and Labour Markets: Explaining Cross-National Patterns of Far Right Party Success in European Parliament Elections. Jcms-Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(3), 636–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12310

19) Jolly, S., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2022). Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999- 2019. Electoral Studies, 75(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420

20) Kitschelt, H., & McGann, A. J. (1995). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. University of Michigan Press.

21) Kriesi, H., & Schulte-Cloos, J. (2020). Support for radical parties in Western Europe: Structural conflicts and political dynamics. Electoral Studies, 65, 102138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102138

22) Lancaster, C. M. (2019). Not So Radical After All: Ideological Diversity Among Radical Right Supporters and Its Implications. Political Studies, 68(3), 600-616. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719870468

23) Martínez-Gallardo, C., Cerda, N. de la, Hartlyn, J., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Bakker, R. (2022). Revisiting party system structuration in Latin America and Europe: Economic and socio-cultural dimensions. Party Politics, 29(4), 780-792. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221090604

24) Mazzoleni, O., & Ivaldi, G. (2020). Economic Populist Sovereignism and Electoral Support for Radical Right-Wing Populism. Political Studies, 70(2), 304-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720958567

25) Morán Faúndes, J. M. (2023). ¿Cómo cautiva a la juventud el neoconservadurismo? Rebeldía, formación e influencers de extrema derecha en Latinoamérica. methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 11(1), m231101a05. https://doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v11i1.649

26) Mudde, C. (2013). Three decades of populist radical right parties in Western Europe: So what? European Journal of Political Research, 52, 1-19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02065.x

27) Mudde, C., & Rovira, C. (2019). Populismo: Una breve introducción. Alianza Editorial.

28) Muis, J., & Immerzeel, T. (2017). Causes and consequences of the rise of populist radical right parties and movements in Europe. Current Sociology, 65(6), 909–930. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392117717294

28) Nicoli, F., & Reinl, A.-K. (2020). A tale of two crises? A regional-level investigation of the joint effect of economic performance and migration on the voting for European disintegration. Comparative European Politics, 18(3), 384-419. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00190-5

30) Olmos Alcaraz, A. (2023). Desinformación, posverdad, polarización y racismo en Twitter: análisis del discurso de Vox sobre las migraciones durante la campaña electoral andaluza (2022). Methaodos Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 11(1), m231101a09. https://doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v11i1.676

31) Rama, J., & Cordero, G. (2018). Who are the losers of the economic crisis? Explaining the vote for right-wing populist parties in Europe after the Great Recession. Revista Espanola De Ciencia Politica-Recp, 48, 13-43. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.48.01

32) Rodrik, D. (2011). The Globalization Paradox. Norton & Company, Inc.

33) Rodrik, D. (2018). Populism and the economics of globalization. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(1), 12-33. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-0001-4

34) Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351- 368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000145

35) Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A. L. P., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., Van Kessel, S., De Lange, S. L., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList: A Database of Populist, Far-Left, and Far-Right Parties Using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC). British Journal of Political Science, 1- 10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431

36) The World Bank. (n.d.). Gini Index. Retrieved May 13, 2024, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI

37) Ubilluz Raygada, J. C. (2021). Sobre la especificidad de la derecha radical en América Latina y Perú. De Hitler y Mussolini a Rafael López Aliaga. Discursos Del Sur, Revista de Teoría Crítica En Ciencias Sociales, 7, 85–116. https://doi.org/10.15381/dds.n7.20903

38) United Nations. (n.d.). International Migrant Stock. Retrieved July 20, 2024, from https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

39) van der Waal, J., & de Koster, W. (2018). Populism and Support for Protectionism: The Relevance of Opposition to Trade Openness for Leftist and Rightist Populist Voting in The Netherlands. Political Studies, 66(3), 560-576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717723505

40) Zanotti, L., Rama, J., & Tanscheit, T. (2023). Assessing the fourth wave of the populist radical right: Jair Bolsonaro’s voters in comparative perspective. Opiniao Publica, 29(1), 1– 23. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-019120232911

1) Western Europe is considered as the countries that formed the original EU-15: Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), Denmark (DK), Finland (FI), France (FR), Germany (DE), Greece (GR), Ireland (IE), Italy (IT), Luxembourg (LU), Netherlands (NL), Portugal (PT), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), and United Kingdom (UK).

2) Henceforth, Table A1 lists the ultranationalist political parties in Western Europe (in their native names and in English) with at least one Member in the European Parliament resulting from the elections held in June 2024, and which have been registered in a group in the constitution of the tenth legislature.

3) The Left: The Left Group; S&D: Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats; Greens: Group of the Greens; Renew: Renew Europe Group; EPP: Group of the European People’s Party; ECR: European Conservatives and Reformists Group; Patriots: Patriots for Europe; ESN: Europe of Sovereign Nations; NI: Non-attached members.

4) The Madrid Charter is a document "in defense of freedom and democracy in the Iberosphere" signed on October 26, 2020, in Madrid, promoted by Disenso (foundation dependent of the Spanish ultranationalist party Vox).

5) Data corresponding to 2020 (latest available data). Luxembourg has not been included not to distort the data presented despite its small size.

6) In all countries, the latest year available has been used. In all cases it is the year 2021 with some exceptions. The latest available data for Honduras is the year 2023. In the case of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay, the latest available data is from 2022. In the cases of Germany and Honduras the information dates from 2019. Information from Guatemala, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Venezuela has not been included due to outdated data (2014 in the first two cases; 2012, in the case of Haiti; and 2006, in Venezuela).

Matamoros-Becerra, Javier

Javier Matamoros Becerra is PhD Candidate in the Economics and Business Program at the University of Extremadura. Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration and Management from the University of Extremadura. Completed a six-month predoctoral research stay at the Department of Political Science, University of Iowa, through the FULBRIGHT program (2023). Since January 2021, serves as Lecturer in the Department of Financial Economics at the University of Extremadura. Recipient of the European Research and Mobility Grant in European Studies "Carlos V Award" (2023). His primary research focus is the analysis of the relationship between economic globalization and the resurgence of ultranationalism in Western Europe.