Museum brand identity model approach: An online Delphi Study

Planteamiento de un modelo de identidad de marca museo: Un estudio Delphi online

Autores

Ferreiro-Rosende, Erica

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1039-6179

University of Alicante, Spain

Datos del artículo

Año | Year: 2022

Volumen | Volume: 10

Número | Issue: 1

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v10i2.544

Recibido | Received: 12-2-2022

Aceptado | Accepted: 22-3-2022

Primera página | First page: 160

Última página | Last page: 176

Resumen

Museum brand management is a practice increasingly used in the museum sector, at least at a primary level. The scarce academic literature on the subject has created the opportunity to approach museum brand management from a deeper perspective, including its brand identity. For this purpose, an online Delphi study consisting of three rounds of questions was developed. A total of 12 experts, from the public and private sector, as well as academia, participated in the process, which was carried out between 2019 and 2021. The main objective was to identify a brand identity model for museums and its adaptability to the post-COVID era from a theoretical point of view. The main dimensions that compose the agreed model are: the product, the person, the symbol, the organisation, the territory and the digital sphere. According to the experts, this model is versatile enough to be adapted to all museums, regardless of their type and size/structure. This study provides a theoretical validation of a brand identity model, and it also demonstrates a growing focus on marketing and brand management by experts and academics.

Palabras clave: gestión de marca, identidad de marca, COVID-19, branding de museo, métodos cualitativos,

Abstract

La gestión de marcas museo es una práctica cada vez más utilizada en el sector museístico, por lo menos en un nivel primario. La escasa literatura académica sobre el tema ha creado la necesidad de abordar la gestión de marcas museo desde una perspectiva más profunda, incluyendo su identidad de marca. Para ello se ha llevado a cabo un estudio Delphi online compuesto por tres rondas de preguntas. Un total de 12 expertos, procedentes del sector público y privado, así como del mundo académico, participaron en el proceso que se llevó a cabo entre 2019 y 2021. El principal objetivo ha sido identificar un modelo de identidad de marca para museos y su adaptabilidad a la era post-COVID desde un punto de vista teórico. Las principales dimensiones que componen el modelo consensuado son: el producto, la persona, el símbolo, la organización, el territorio y el ámbito digital. Según los expertos, este modelo es lo suficientemente versátil como para adaptarse a todos los museos, independientemente de su tipo y tamaño/estructura. Este estudio proporciona una validación teórica de un modelo de identidad de marca, y también demuestra una creciente atención al marketing y branding por parte de expertos y académicos.

Key words: brand management, brand identity, COVID-19, museum branding, qualitative methods,

Cómo citar este artículo

Ferreiro-Rosense, E. (2022). Museum brand identity model approach: An online Delphi Study. methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 10(2): 160-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v10i2.544

Contenido del artículo

1. Introduction

Brand identity can be defined as a unique set of associations that the strategist aims to create or maintain (Aaker, 1996)Ref1 which is utilised as an essential tool to differentiate and manage brands (Da Silveira, 2013).Ref20 Due to its abstract nature and the breadth of disciplines to which it can be applied, brand identity has been studied by several authors (Aaker, 1996Ref1; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Ghodeswar, 2008Ref27; Kapferer, 1992Ref31; Urde, 2013Ref52) who offer multidimensional models and processes with more theoretical than empirical results (Coleman et al., 2011)Ref17. Although some authors focus the main elements of brand identity on its most visual part, such as the logo, taglines, colours, or characters (Ward et al., 2020)Ref57, brand identity goes much further. In fact, several of these models combine internal factors, such as the product, the personality, the organisation, and its culture and values, or the employees themselves, with factors external to the institution such as relationships with different audiences, the image, or the communication of the brand message. The evolution of the term is not so much towards a static and fixed brand identity, but rather a dynamic process (Essamri et al., 2019)Ref22 in which it can adapt to the passage of time, changes in the environment, and other factors such as consumers (Da Silveira et al., 2013)Ref20.

Although marketing is a well-established tool, branding and brand identity management has been timidly entering the museum sector in recent decades. Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of brand-oriented management that can help not only to increase visitor numbers, but also visitor familiarity and loyalty (Ajana, 2015)Ref2; connect with the community (Scott, 2007)Ref48; convey trust to attract funding (Pusa & Uusitalo, 2014Ref42; Belenioti et al., 2017Ref6); improve the internal management of the museum (Scott, 2007)Ref48, and assure sustainability (Belenioti et al., 2017)Ref6. The relationship between brand and museum has developed to the point that aside from the business world moving into museums, museums have also started to become a heritage tool for brands (Iannone and Izzo, 2017Ref29; Chaney et al., 2018Ref13). In this regard, local authorities have opted for the opening of a branch of a famous museum as a tool for urban regeneration in order to be more competitive (Vivant, 2011)Ref54. The most famous museums are not the only ones that need to make an effort in their brand management, lesser-known museums also need to build a strong brand (Cole, 2008)Ref16 to be understood by their visitors. This marketing trend has evolved differently in this apparently globalised world. While Anglo-American model, which prevails in British, American and Australian museums (Camarero et al., 2016Ref10; Massi & Harrison, 2009Ref37), pursues a more commercial and self-sufficient trend, in Europe (Continental European model) there is still a heavy reliance on public funding (Vicente et al., 2012)Ref53, preceded by a long-standing traditional past linked to a curational orientation. In fact, some authors (Belenioti et al., 2017Ref6; Recuero Virto et al., 2017Ref44) suggest the combination of curational orientation with brand-oriented management, although empirical studies in the sector are still rather scarce.

After the worldwide pandemic caused by COVID-19, the cultural sector has suffered a severe impact (Cecilia, 2021)Ref12. Museums in 2020 have had to modify their access channels to adapt to the reality derived from the strong restrictions for health reasons and then focus their efforts on living with the current ever-changing reality. The most recent publications on museums have focused mainly on changes at the educational (Samaroudi et al., 2020)Ref47, inclusive (Cecilia, 2021)Ref12, economic (Antara & Sen, 2020)Ref3 and digital (Choi & Kim, 2021Ref15; Crooke, 2020Ref19; Corona, 2021Ref18; Kist, 2020Ref32; Zollinger, 2021Ref58) level, covering both public and private spheres. These changes affect the brand identity of museums and how their mission is conveyed in the new post-pandemic era.

Within this context, the aim of this study is proposing a theoretical contribution to researchers and professionals from a strategic point of view. To this end, and based on previous brand identity models, the aim is to reach a consensus, through the opinion of academic and professional experts, on a model that covers all those aspects that museums could reinforce when building a strong brand. Despite several studies supporting the advantages of applying branding tools in museums (Stallabrass, 2014Ref49; Vivant, 2011Ref54), theoretical and empirical studies specific to this sector are still scarce, especially studies that have applied brand identity models in museums (Ferreira, 2012Ref24; Ferreiro-Rosende et al., 2021Ref25; Pusa & Uusitalo, 2014Ref42). Although this study was initiated before the pandemic, the new situation has allowed a broader analytical context to be generated. In this way, it has been possible to reinforce and adapt the consensus reached before COVID-19 to the new, still changing, reality of museums.

This research makes some important contributions to the existing literature. It considers previous brand identity models and proposes a new framework that encompasses all those aspects that can compose the museum brand. To this end, it was appropriate to consider the point of view of several experts in the sector, both public and private, not only on the current situation of museums in terms of brand management, but also on the applicability of a brand identity model and its suitability in this post-pandemic global phase. Moreover, the results obtained offer support to museum managers in establishing management tools and instruments based on the attributes that make up the brand identity of each museum. Defining its main dimensions will allow them to direct and optimise their resources from the inside out, from their mission to the museum's relations with the environment and the various stakeholders.

2. Reconceptualising a museum brand identity model: a new post-pandemic scenario

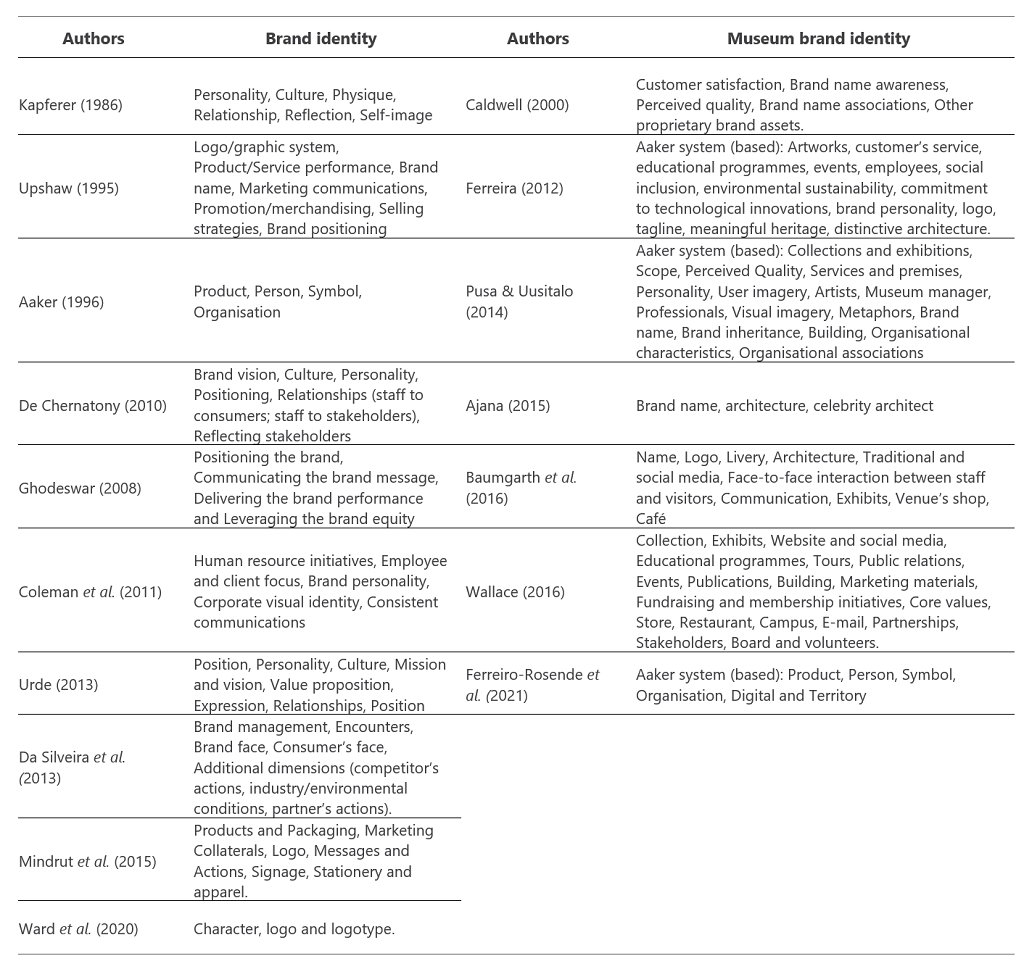

In the literature covering the concept of brand identity over the last few decades, researchers have been shaping their proposals towards a more dynamic version (Table 1).

The brand itself is no longer understood as an image whose shape, colour and design must be defined, but encompasses all those aspects that the organisation intends to convey. Although there is a trend of study on the co-creation of brand identity between the organisation and consumers or other stakeholders (Coleman et al., 2011Ref17; Da Silveira et al., 2013Ref20; Essamri et al., 2019Ref22; Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2018Ref43; Von Wallpach et al., 2017Ref55) certain common aspects can be observed in the systems proposed that still focus on the most internal part of the institution.

This is in line with Baumgarth et al. (2016)Ref5 who differentiated marketing from branding by determining that the marketing has a clear orientation towards the visitor from which the strategies to be followed emerge, while branding has an orientation from the inside out. For this reason, brand identity should be the starting point, created and composed of the most internal attributes of the organisation, which will guide the management and strategies to be followed for its dissemination to the market.

In this way, dimensions such as brand personality (Aaker, 1996Ref1; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Coleman et al., 2011Ref17; Kapferer, 1986Ref31; Urde, 2013Ref52) that can be linked to a character (Aaker, 1996Ref1; Ward et al., 2020Ref57); the most visual part (Aaker, 1996Ref1; Coleman et al., 2011Ref17; Kapferer, 1986Ref31; Mindrut et al., 2015Ref38; Upshaw, 1995Ref51; Urde, 2013Ref52; Ward et al., 2020Ref57); the product or service (Aaker, 1996Ref1; Ghodeswar, 2008Ref27; Mindrut et al., 2015Ref38; Upshaw, 1995Ref51); or those values related to the organisation (Aaker, 1996Ref1; Coleman et al., 2011Ref17; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Kapferer, 1986Ref31; Urde, 2013Ref52) are commonly repeated by the various researchers over the years.

The literature on brand management in museums, which has emerged in the last two decades, does provide us with various items or points of contact that museums should take into account when managing their brand identity, such as the brand name, the collection, architecture, digital communication, events, educational programmes, social inclusion or complementary services such as the shop or the restaurant. The main empirical applications of the concept of brand identity in the museum sector are provided by studies such as Pusa & Usuitalo (2014)Ref42 in two Australian museums or Ferreiro-Rosende et al. (2021)Ref25 in the case of artist museums. In both cases, the brand identity system applied is based on the one proposed by Aaker (1996)Ref1, also used in other sectors (Carter, 2003Ref11; Mariutti & Giraldin, 2014Ref36; Moorthi, 2002Ref40), which demonstrates its wide adaptability.

Nevertheless, the “new normal” scenario presents different circumstances which make that well-known models as the one proposed by Aaker need to be re-formulated. Furthermore, the current situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has meant that museums had to reinvent themselves during the year 2020 to offer their content in a different way. Thus, in record time, the world's major museums began to disseminate their collections, seeking constant interaction with and participation from their public. In recent decades, technology has influenced social communication (Corona, 2021)Ref18 and the evolution of digital usage has increased dramatically since the year 2020 (Antara & Sen, 2021)Ref3, impacting the working, social, and educational lives of millions of people (Samaroudi et al., 2020)Ref47. Although museum communication through tools, such as the web and social media, is not a new development, changes are currently taking place in museum investment in digital content, engagement, and infrastructure (Kist, 2020)Ref32. Enabling online access to such institutions could not only keep them active, but also reduce the isolation of the public, improve their mental health, and support their creative and educational needs (Samaroudi et al., 2020)Ref47. As Choi and Kim (2021, p. 1)Ref15 point out “digitalisation improves the quality of the experience for visitors, makes museums accessible to more visitors, and promotes the use of the values and assets of museums in a wider variety of fields”. However, this has also raised concerns about the role of social media in museums in instigating critical thinking and reflections during and after COVID-19 (Kist, 2020)Ref32. In this sense, museums may provoke critical reflections through challenging heritage as long as it is aligned with their mission and social goals. Although the pandemic caused by COVID-19 seems to be coming to an end, for museums it has meant a structural change and, therefore, an adjustment in the management of their brand identity that will need to be studied.

3. Methodology

The objective of this study focuses on reaching a consensus among experts in the field to accept a brand identity model adapted to the museum sector.

The main characteristics of the Delphi method include its iterative nature, its anonymity, controlled feedback, and the statistical response of the group (García & Suárez, 2013Ref26; Landeta, 1999Ref33; Reguant-Alvarez & Torrado-Fonseca, 2016Ref45). Its applicability in multiple disciplines such as education (Bravo & Arrieta, 2005)Ref7, tourism (Chim-Miki & Batista-Canino, 2018)Ref14 and health (García & Suárez, 2013)Ref26, among others, makes it an increasingly common practice. The main limitation of this methodological process is the subjectivity of the people guiding the study, both when setting up the initial questionnaire and when guiding the successive consultations, as the researcher acts with considerable autonomy. For this reason, this process can be more intuitive than rational (Astigarraga, 2003)Ref4.

3.1. Participant selection process

A panel of twenty-one experts was chosen, justified by two fundamental aspects:

1. National and international recognition in the academic field, since the main approaches to the object of study have been made from a theoretical point of view. The main authors on museum branding studies were invited, as well as academics involved in the sector whose knowledge has contributed to the field of study.

2. Experts of recognised national and international prestige in the professional field, including cultural managers, directors, and heads of museum departments. Although all the experts share a common link with museums and their brand, the panel offers heterogeneous profiles that add richness to the study.

In addition to academic and professional background, aspects such as years of experience, publications related to the subject, links with organisations related to the sector, etc., were also taken into account. To ensure freedom of opinion and participation in the study, the responses were completely anonymous in order to eliminate the leader effect or the influence of opinion of influential people in the sector. Once the panel of experts had been decided upon, they were contacted by email, a tool used throughout the process, for an initial approach to the study, at which point they decided to accept or reject their participation. Of the twenty-one experts contacted, twelve finally participated in the study (six from academia with expertise in museology, heritage management, digital culture, and cultural heritage marketing; three experts from the private sector from cultural consultancies, digital content and audience management; and three from the public sector including museum management and communication department heads), the size of which is in congruence with previous studies that advise a minimum of seven and a maximum of thirty participants (Astigarraga, 2003Ref4; Landeta, 1999Ref33; Reguant-Alvarez & Torrado-Fonseca, 2016Ref45).

3.2. First round

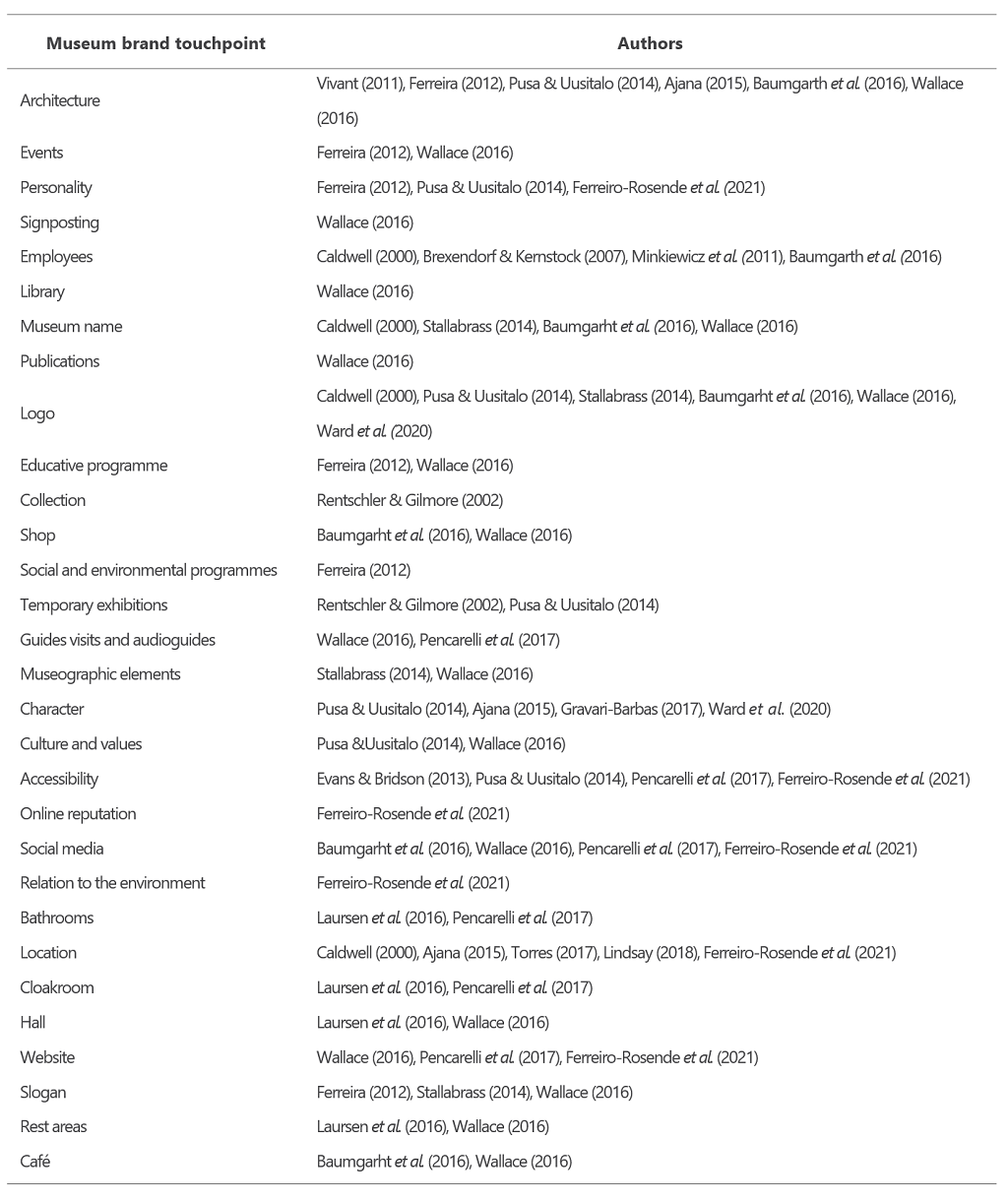

A questionnaire for the first round was designed with precise, quantifiable and independent questions (Astigarraga, 2003)Ref4 derived from the literature on museums and museum branding in order to include all those variables that could be relevant to the brand identity management system. This phase started with a global assessment of the situation of museums in terms of brand identity management. The questionnaire consisted of nine questions, eight closed-ended and one open-ended. The closed-ended questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale, a common method of data collection in the social and human sciences. One of these questions was the assessment of thirty brand touchpoints (Table 2)Ref23, drawnRef34 from the academic literature, through which museums have a relationship with their different stakeholders. In addition, open-ended comments were allowed at the end of each question in order to obtain new indicators that were not present in the reviewed literature. The first round was carried out in April 2019, allowing a period of two months to receive the responses.

3.3. Second round

Once the results of this first round had been analysed, a second questionnaire was sent out in July 2019, preceded by a summary of the results obtained in the first round. The second round provided feedback from the first consultation to form the basis for discussion and consensus on the results. This new questionnaire presented nine Likert-scale questions with the possibility of providing a personal opinion after each one, thus favouring a qualitative analysis of the results. After a further two months, the results were analysed. The objectives of this second round focused on confirming the validity of the model extracted from the results of the previous round. In addition, thanks to the assessment and comments of the experts in the last part of the round, it was possible to clarify its applicability to the sector, taking into consideration the size/structure and typology of the museums.

3.3. Third round

Although the purpose of the study was accomplished in the two previous rounds, thus obtaining a complete model that included all the most relevant aspects of the brand identity of a museum, at the beginning of 2020 a new situation derived from COVID-19 which affected all sectors, including museums. For this reason, and taking advantage of the Delphi study, a third round was launched in March 2021 with a single open-ended question. In it, the experts were asked whether the model agreed upon in the previous rounds conforms to the current situation, or whether it was necessary to include or modify any of the dimensions proposed. The Delphi study was concluded in June 2021 with the conclusions presented below.

The responses to the questionnaires submitted in the three rounds made it possible to carry out a quantitative analysis for the closed-ended questions and a qualitative analysis for the open-ended questions. A descriptive statistical analysis was performed using measures of central tendency and dispersion such as mean, mode, and standard deviation, commonly used in the analysis of Delphi results (Chim-Miki & Batista-Canino, 2018Ref14; Renguant & Torrado, 2016Ref45). On the other hand, through the Atlas.ti software, increasingly used in qualitative studies, a segmentation and coding of the responses obtained was executed in order to increase the value of the analytical procedure. The responses were grouped into open codes, previously identified from existing theory, and in vivo codes. In turn, the codes were grouped into families and axial coding allowed the search for the relationship between them. Therefore, the experts' answers to the open questions, the assessment of the items, and the bibliographic review of the literature made it possible to configure the dimensions and interconnections of the final model.

4. Results

From the 1experts' initial reflection on the status of brand identity management in museums, two fundamental aspects emerge: On the one hand, there is a broad consensus that museums should build a brand identity based on the mission, which conveys the values of the organisation and which is communicated and disseminated to actual and potential visitors.

The museum sector should make an effort to strengthen brand management because this will be a great help for its promotion and dissemination. There is still much to be done and museums are gradually becoming aware of the importance of branding. (E1) It is essential that museums work on identity and brand management, very much in line with the Anglo-Saxon approach. (E2)

However, the reflection that has arisen regarding today’s brand management reality is that due to budgetary problems suffered by many museums, especially those less well-known, it has not been possible to orient their strategy towards marketing or branding. Therefore, it can be determined that, despite the fact that experts endorse the effectiveness and necessity of applying marketing and branding strategies in museums, the reality is that there is still no generalised trend in the sector.

Brand identity is important because it allows the values that the institution considers its own, and that it wants its community to be part of, to be transmitted. But, knowing the budgetary problems of most national museum institutions, it is easy to understand why, with a few exceptions, not all the necessary effort is made. (E3)

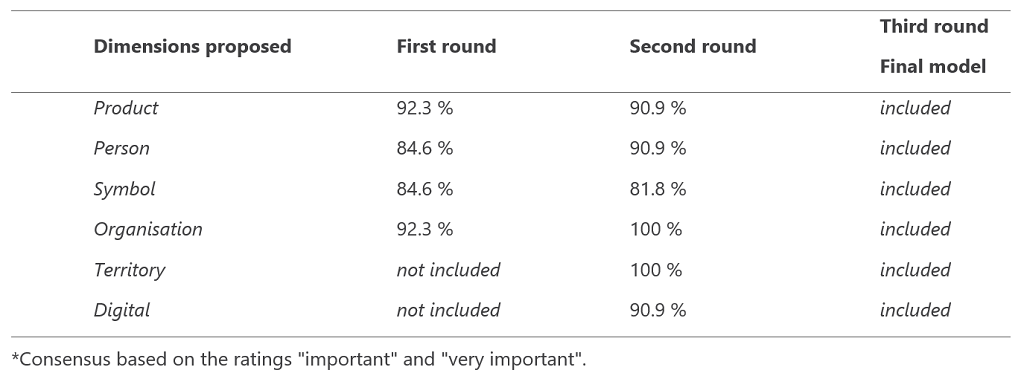

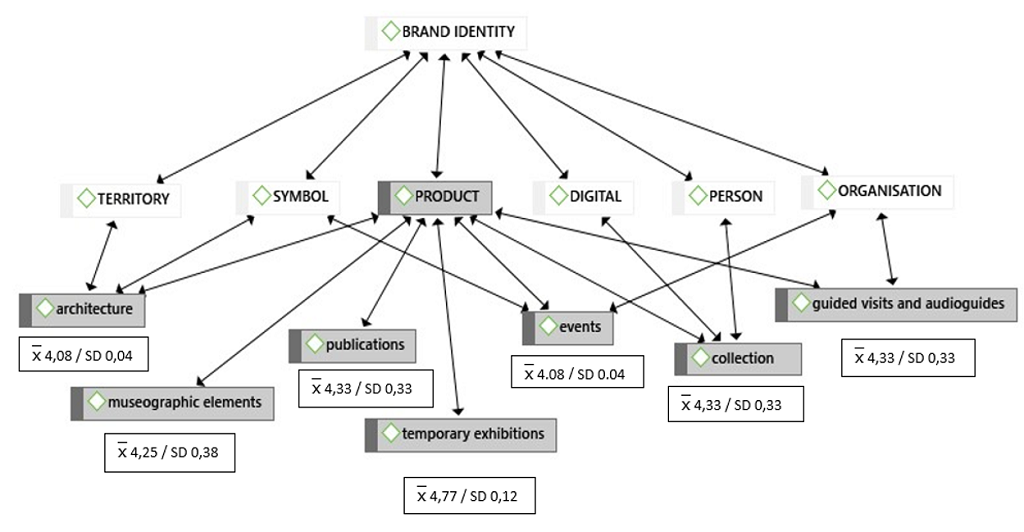

The results shown below reflect the consensus reached in the three rounds of the study in order to facilitate understanding of the final model. In addition, nine of the thirty items rated by the experts were discarded as most of them scored below 4. These items were the rest areas, the café, the hall, the shop, the toilets, the library, the slogan, signposting, and the cloakroom. The remaining items were grouped according to the product, symbol, person, organisation, territory and digital dimensions. The second and third rounds confirmed the proposed model (Table 3).

4.1. Product

The results of the three rounds of the study reflect that the product dimension, present in most brand identity models (Aaker, 1996Ref1; Pusa & Uusitalo, 2014Ref42; Upshaw, 1995Ref51), is composed of seven main touchpoints (Figure 1). During the first round, 92.3% consensus was reached and supported by 90.9 % in the second round.

The collection and temporary exhibitions are the most tangible part of a museum's product and, in many cases, they are the main reason for visiting the museum (Rentschler & Gilmore, 2002)Ref46. Moreover, especially in art museums or monographic museums, the collection can also be related to a relevant character, such as a reference artist who is a fundamental part of the brand identity. On the other hand, the architecture can be considered as another work of art (Vivant, 2011Ref54; Wallace, 2016Ref56) and part of the main product, with statements such as:

It is clear that the collection is essential to the museum and that the brand identity must always accompany temporary exhibitions and all museum-related events. But at the same time, the museum's architecture itself is nowadays highly valued as a work of art. (E2)

The collection has been linked to the digital sphere for years, as many museums offer their catalogue online. The pandemic caused by COVID-19 has led to a reflection on how to approach the museum product.

We can no longer be content with planning large exhibitions, but must focus much more on the collections themselves, many of which are unknown to the general public, and present them in a more didactic and meaningful way. We need museums that are more sensitive to the needs of society, more supportive, plural, inclusive and creative, that are willing to break with old patterns and provide new visions, closer to the reality we live in. (E10)

Finally, the museographic elements, the publications, the audio guides, and the guided tours, or even the events, are aspects to be taken into consideration by museum managers in order to increase the value of the main product and make the visitor's experience more productive (Wallace, 2016)Ref56.

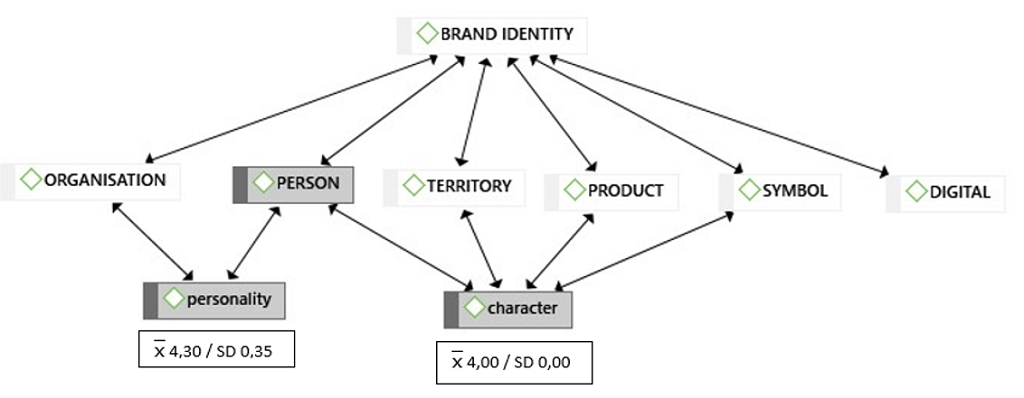

4.2. Person

The brand as a person, which includes the personality of the brand, has also generated a large consensus (90.9%), although in the first round (84.6%), the term caused some confusion. Brand personality has been present in many brand identity models (Aaker, 1996Ref1; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Kapferer, 1986Ref31; Urde, 2013Ref52) and introduced in the museum sector also by authors such as Ferreira (2012)Ref24, Pusa & Uusitalo (2014)Ref42, or Ferreiro-Rosende et al. (2021)Ref25

Obviously, the term was ambiguous, but there is no doubt that a brand with personality, firm, open, creative, and with a future dimension can enrich the life and dynamics of the museum. (E2)

The fact that brands are attributed personal qualities means that they are endowed with a personality that evokes a feeling of closeness and empathy in consumers. This personality can be closely related to the organisation and its employees through their behaviour, for example (Figure 2). In fact, characters associated with a brand generate a humanistic visual representation of the brand (Ward et al., 2020)Ref57. Yet, this dimension is more evident in museums that are associated with a remarkable character, artist, or architect (Gravari-Barbas, 2017Ref28; Pusa & Uusitalo, 2014Ref42; Vivant, 2011Ref54). The character not only lends value to the brand, but can be the core of the museum's brand identity (Ferreiro-Rosende et al., 2021)Ref25 and even influence the appreciation of the collection. In fact, the character can be intimately linked to the territory or be part of the symbolism of the museum brand through, for example, its name.

Art museums (and to a lesser extent monographic museums) are more dependent on certain aspects: product, collection and exhibitions, building, person (in terms of names of artists who are brands in themselves). (E4)

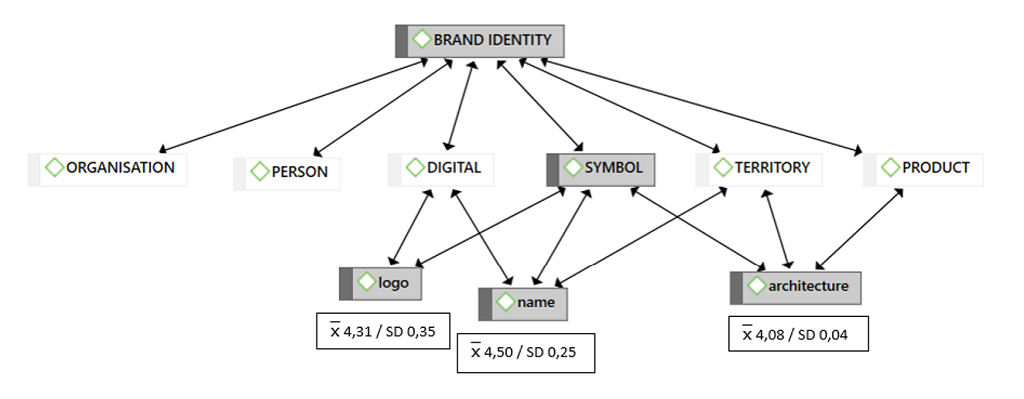

4.3. Symbol

The clearest and most evident representation of dimension of brand identity is the symbol (Aaker, 1996Ref1; Coleman et al., 2011Ref17; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Kapferer, 1992Ref31). Ward et al. (2020)Ref57 determine that a strong brand identity should comprise unique identity elements such as a logo, colours, or characters that make it recognisable from its competitors and encourage purchase. In the same vein, Baumgarht et al. (2016)Ref5 states that the first point of contact with a cultural institution is its brand name, logo, livery, or architecture. Although this study addresses more dimensions of brand identity, we agree that its more visual part must be present, with a high degree of consensus in both the first round (84.6%) and the second round (81.8%).

The brand name is a fundamental part of the digital sphere, as it is what gives the museum its name in its digital dissemination. In addition, many museums include in their name the place where they are located, generating a museum-territory brand link. The logo is an element traditionally used in marketing and branding strategies that conveys the brand's promise and heritage (Wallace, 2016)Ref56, and is the brand element with the highest concentration of uniqueness (Ward et al., 2020)Ref57. These aspects also form a fundamental part of the digital sphere (Figure 3), which often features a design that is coordinated with the museum's visual identity.

The symbolic capacity of any brand within the museum can become a renovating and transforming instrument of the idea of the museum. (E2)

Architecture, especially through the building or the façade, can further generate symbolism in the minds of visitors (Pusa & Uusitalo, 2014)Ref42. One of the experts (E6) referred to the well-known case of the Guggenheim Bilbao, highlighting its architecture as a fundamental part of its brand identity, not only at a product level, but also as a symbolic association which can also be intimately linked to the territory and its destination brand (Figure 3).

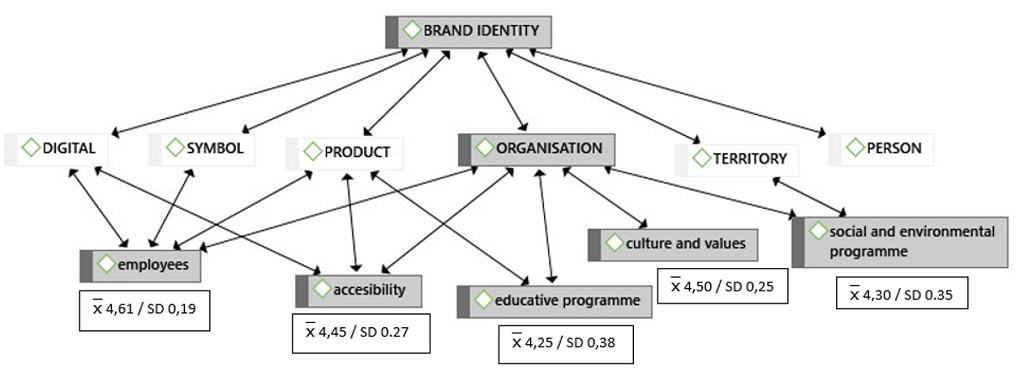

4.4. Organisation

The results of the three rounds of the Delphi study show that the organisation strengthened its presence in the final model from 92.3% consensus in the first round to 100% in the second round. Organisation is also a frequent factor in the brand identity models proposed in the literature through items such as culture (Aaker, 1996Ref1; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Kapferer, 1986Ref31; Urde, 2013Ref52), brand vision (De Chernatony, 2010)Ref21 or company employees (Coleman et al., 2011Ref17; Da Silveira et al., 2013Ref20; De Chernatony, 2010Ref21; Wallace, 2016Ref56). The results identify six main brand touchpoints (Figure 4), highlighting the culture and values of the museum and its employees.

The idea of creating one's own culture is reinforced in order to escape from a globalised approach without identity. This leads to the need for qualified staff, both in the museum offline and online, as they are the embodiment of the brand (Brexendorf & Kernstock, 2007)Ref8. Employees, through their uniforms and their behaviour, are key for consumers to perceive the organisation's identity (Minkiewicz et al., 2011)Ref39. Baumgarth et al. (2016)Ref5 also establish face-to-face interaction between employees and visitors as a brand touchpoint.

The involvement of qualified museum staff is fundamental for the relationship between the institution and the public to be truly effective. Only through such intercommunication is it possible for there to be a mutual enrichment that favours people's personal involvement in the museum's projects and activities. (E2)

Furthermore, the experts referred to a current problem regarding employees, although they play an important role in the digitalisation process stemming from COVID-19 crisis.

What happens is that many museums leave the question of personnel to external companies or contractors, losing a fundamental value. (E6) This new digital aspect requires a strategy that involves the entire staff and an organisation that makes the digital channel one of the fundamental pillars of the museum, generating a brand image that can be as productive as the live viewing of the works themselves. (E3)

In addition, the organisation may also have socially-focused values, such as social and/or environmental programmes, it may focus on the local community by offering educational programmes, visiting facilities for local groups, etc. These organisational values can change the image of the museum as a driver of its brand identity.

The Delphi study concluded that the museum sector has some particularities to be considered. The open-ended questions proposed in the first round suggest two main ideas:

1. The importance of linking the museum brand with its territory or region, achieving harmony with the environment that makes it feel its own, establishing an emotional link and a sense of belonging.

2. The importance of communication with special emphasis on "tone" and "emotional content". Thus, communication through tools such as storytelling, digital communication, or the treatment of the public by museum staff were mentioned as elements that differentiate the museum from other organisations.

For that reason, two more dimensions were added: the territory and the digital dimension.

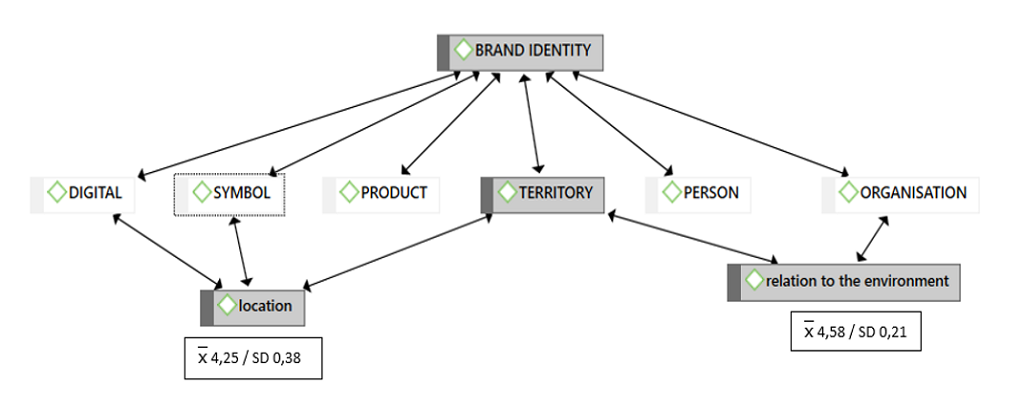

4.5. Territory

With a consensus of 100%, this dimension was reaffirmed in the second round. Although Aaker (1996)Ref1 alludes to the environment and location of the company as part of the product perspective (Moorthi, 2002Ref40; Carter, 2003Ref11), the link between the museum and its environment on a historical and emotional level must be treated and managed with special interest. Caldwell (2000)Ref9 has already pointed out the significant role that location plays for museums as tourist destinations. Indeed, on a more general level, cultural tourism itself fosters territorial identity while strengthening cohesion between regions and favouring heritage diversity (Torres, 2017)Ref50.

A museum cannot live with its back turned to the reality that surrounds it because it is part of the same socio-cultural context in which it is located and carries out its cultural activity. (E2) In the case of museums in non-touristic territories, the museum team, the product (whether participatory or not), and the relationships with the environment are the fundamental elements. (E4)

As some experts point out, the local population and the environment can be a fundamental part of the brand identity of a museum. In fact, mutual collaboration allows to promote the dissemination of the message and to reinforce that identity. This is in accordance with several studies that argue for the role of museums in strengthening the idea of nationhood (Lindsay, 2018)Ref35, creating a sense of community (Ajana, 2015)Ref2, or even enhancing the territory's reputation as a lively place to live in and to visit (Vivant, 2011)Ref54. However, there has also been some, albeit minority, opinion on the risk of museums becoming more localised, as this may influence the loss of audiences and funding (Figure 5).

4.6. Digital

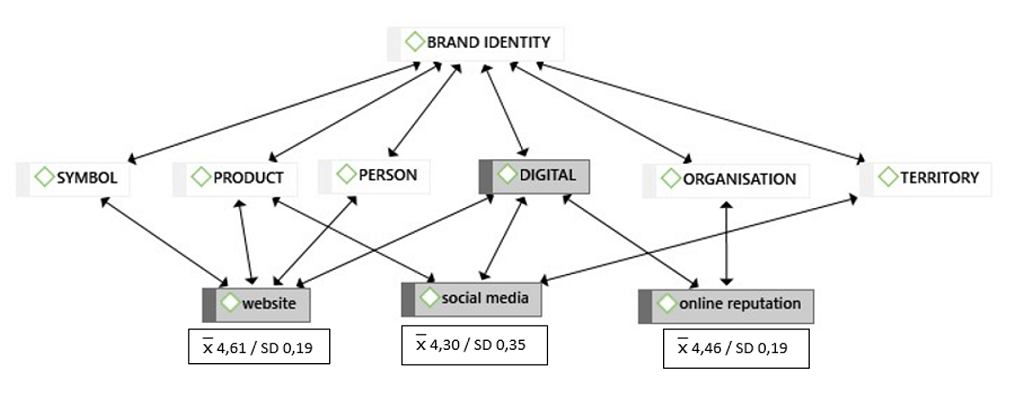

The results of the first round showed the need to accommodate digital spaces, which can include the museum's website, social media, and even online reputation management. This dimension has appeared occasionally in some brand identity models, especially in more recent studies (Baumgarth et al., 2016Ref5; Ferreiro-Rosende et al., 2021Ref25; Wallace, 2016Ref56).

The digital sphere must be present for four main reasons: to influence a large number of people, to enrich visitors' knowledge of the museum, to to be involved in the co-creation of communication (Pencarelli et al., 2017)Ref41 and, to generate a stimulus for their visit (Kabassi, 2017)Ref30. Even so, despite a 90.9% consensus, several experts pointed out that this medium should not be an end in itself, and that it is important not to put digital before analogue.

Today the museum cannot turn its back on digital spaces. On the contrary, it has to get involved in a very direct way in their use because it is one of the most direct ways of influencing a large number of people who look at the Internet and access its contents. (E2)

This dimension strengthened its presence in the final model with the third round conducted in 2021. After the pandemic caused by COVID-19, it was precisely the digital sphere that came out stronger, especially in relation to two aspects: strengthening the collections themselves instead of organising large exhibitions, and communicating through social media. The experts' opinions are in line with recent studies (Crooke, 2020Ref19; Antara & Sen, 2021Ref3; Choi & Kim, 2021Ref15) that state that museums' digital strategy is definitely here to stay. (Figure 6).

At the same time as there has been a physical distancing, there has been an increased need for a rapprochement through different channels such as digital channels, which already existed but which required an important intellectual and economic effort, something that is not within the reach of all budgets. (E9)

This dimension is interconnected with the other dimensions through its items as it is the window to the online museum. Moreover, it is one of the touchpoints that not only allows the dissemination of information and news about the museum, but there is also a two-way communication that seeks the loyalty of its followers.

4.7. Interconnections and adaptability of the model

The results accept a brand identity model based on six dimensions: product, person, symbol, organisation, territory, and digital. These dimensions, with a general consensus of over 80%, cover all those aspects in which the museum must reinforce its brand. Moreover, the study concludes a high interconnection between the different dimensions, which emphasises the integrity of the model. The product, the territory, and the digital dimension are those that are most interconnected with the other dimensions, although, depending on the specificities of each museum, these connections will be more or less narrow, or even non-existent. On the other hand, the most connected items are the employees, the website, and the relevant character, which shows the importance of the figure of the employee in the whole museum experience, at a functional and emotional level, as well as the digital bridge as part of the museum's identity, and not only as a communication channel. The employees and the website are also, as well as the exhibitions, the items most highly-rated items by the experts.

In addition, the study reflects that neither size nor typology are variables that can affect the brand identity model, but rather the philosophy of the institution. Regarding size, larger museums with a large volume of visits, and generally a greater financial capacity, work to a greater extent on aspects such as the brand name, the building, or digital spaces than smaller museums with a more local impact. For the latter, their relationship with the environment, the staff, and the collection itself, will be particularly important.

The size of the museum is not important as long as the museum professionals as well as the other people interested in the life of the museum are clearly and resolutely committed to its realisation. (E2)

Furthermore, while typology is a variable that tends to have special relevance in the internal management of museums and, therefore, in their brand as well, all museums can benefit from adapting to this brand identity model.

The system proposed is suitable for all types of museums, provided that the real possibilities of each museum are taken into account and the means are provided to make it possible. (E4)

These reflections only demonstrate the versatility of the system, as the different dimensions make it possible to address all the needs and specificities of each museum, even those emerging from the COVID-19 situation.

The system proposed is therefore very valid as a tool for analysing a new situation that demands new ways of understanding the museum object and its relationship with the visitor. (E6)

5. Discussion

From the results obtained in this paper, the first conclusion is linked with the differences with the previous models. While brand identity has been studied since the 1990s, museum brand identity dates back to the last two decades. For this reason, the studies carried out to date have been based on generalist models that could be adapted to the museum sector. However, and taking into account the specificities of the sector as well as the changes in society, it is appropriate to adapt the bases of the model to today's museums. Thus, in addition to the pre-existing dimensions related to the museum's product, its most visual part, its brand personality, and organisational associations, it is considered essential to include the digital aspect of the brand as well as its link with the territory in which the museum is located. These two dimensions allow, on the one hand, to make the heritage much more accessible, to generate stimuli in users as well as favouring their participation through social media; and, on the other hand, to connect the museum with the identity of the place where it is located, favouring a feeling of belonging and civic pride. These results are in line with the proposal by Ferreiro-Rosende et al. (2021)Ref25, although in their study the dimensions revolve around the brand as a person given its applicability to artist museums. In this case, the aim is to offer a more general model, with a dynamic centred on the mission that substantiates the brand identity and through which the appropriate dimensions are generated.

The second conclusion is related to the new items to be considered under a “new normal” scenario. The figure of the employee has gained strength as a transmitter of brand identity, so it is important to consider their role in this sector, favouring museum policies that include non-externalised management and specialised training. The territory and the digital sphere are also postulated as essential dimensions in the identity of a museum, rooting its mission in the environment and increasing its scope through new technologies, something that emerged more than a decade ago, but is not yet present in a generalised way.

Finally, for the museum sector, COVID-19 meant a complete rethinking of its internal functioning. Two years after the lockdown, and with the museums now open to the public, some of the changes introduced have come to stay. One of the main developments has been the increase in museums' online connectivity as a result of the digital communication boom. This increasingly present dimension has been shown to be a fundamental part of their brand, as it can become a window to potential visitors. Without displacing face-to-face visits, museums have many online options to connect to their visitors, creating a link that allows them to disseminate their mission and objectives.

This research is a contribution to the museum branding literature that should be taken into account for a more efficient management of their museum brands. The proposed model for managing the museum brand (through its product, its person, its symbology, its organisation, its digital sphere, and its link to the territory) allows a sufficient dynamism, broad vision, and level of action to include all types of museums, regardless of their size, structure and typology. Thus, each museum, with its structure and particularities, will reinforce those dimensions and touchpoints that prevail within its institution, without the need for each and every one of them to be present. Following expert validation of this brand identity model, future empirical research could develop more concrete practical implications for each dimension.

The main limitations of the study are due to the particularities of the methodology applied. On the one hand, the subjectivity of the researcher may influence the conduct of the successive rounds. On the other hand, even if the number of experts is adequate for the method applied and a consensus is reached on a particular issue, there may be a tendency to favour the majority opinion. Moreover, given the size of the sample, the results do not necessarily reflect reality. Interviews with museum managers of different sizes and typologies could determine the practical applicability of the proposed model.

Referencias bibliográficas

1) Aaker, D.A. (1996). Construir marcas poderosas. Gestión 2000.

2) Ajana, B. (2015). Branding, legitimation and the power of museums: The case of the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Museums & Society, 13(3), 316-335. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v13i3.333 | https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v13i3.333

3) Antara, N., & Sen, S. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on the museums and the way forward for resilience. Journal of International Museum Education, 2(1), 54-61.

4) Astigarraga, E. (2003). El método Delphi. Universidad Deusto.

5) Baumgarth, C., Kaluza, M., & Lohrisch, N. (2016). Brand audit for cultural institutions (BAC): A validated and holistic brand controlling tool. International Journal of Arts Management, 19(1), 54-99.

6) Belenioti, Z.C., Tsourvakas, G., & Vassiliadis, C.A. (2017). A report on Museum Branding Literature. In Kavoura, A., Sakas, D. P., and Tomaras, P. (Eds.), Strategic innovative marketing (pp.229-234). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56288-9_31 | https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56288-9_31

7) Bravo, M.L., & Arrieta, J.J. (2005). El método Delphi: su implementación en una estrategia didáctica para la enseñanza de las demostraciones geométricas. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 36(7), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie3672962 | https://doi.org/10.35362/rie3672962

8) Brexendorf, T.O., & Kernstock, J. (2007). Corporate behaviour vs brand behaviour: towards an integrated view?. Brand Management, 15(1), 32-40. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550108 | https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550108

9) Caldwell, N.G. (2000). The emergence of museum brands. Marketing Management, 2(3), 28-34.

10) Camarero, C., Garrido, M.J., & San José, R. (2016). Efficiency of Web Communication Strategies: The Case of Art Museums. International Journal of Arts Management, 18(2), 42-92.

11) Carter, S.M. (2003). The Australian cigarette brand as product, person, and symbol. Tobacco Control, 12(3), 79-86. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii79 | https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii79

12) Cecilia, R.R. (2021). COVID-19 Pandemic: Threat or Opportunity for Blind and Partially Sighted Museum Visitors?, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 19(1), Article 5, 1–8. http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.200 | http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.200

13) Chaney, D., Pulh, M., & Mencarelli, R. (2018). When the arts inspire business: Museums as a heritage redefinition tool of brands. Journal of Business Research, 85, 452-458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.023 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.023

14) Chim-Miki, A.F., & Batista-Canino, R.M. (2018). Development of a tourism coopetition model: A preliminary Delphi study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 37, 78-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.10.004 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.10.004

15) Choi, B., & Kim, J. (2021). Changes and Challenges in Museum Management after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation. Technology, Market and Complexity, 7(148), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020148 | https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020148

16) Cole, D. (2008). Museum marketing as a tool for survival and creativity: the mining museum perspective. Museum Management and Curatorship, 23(2), 177-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701865576 | https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701865576

17) Coleman, D., De Chernatony, L., & Christodoulides, G. (2011). B2B service brand identity: scale development and validation. Industrial Marketing Management, 40, 1063-1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.09.010 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.09.010

18) Corona, L. (2021). Museums and Communication: The Case of the Louvre Museum at the COVID-19 Age. Humanities and Social Science Research, 4(1), 15-26. https://doi.org/10.30560/hssr.v4n1p15 | https://doi.org/10.30560/hssr.v4n1p15

19) Crooke, E. (2020). Communities, Change and the COVID-19 Crisis. Museum and Society, 18(3), 305-310. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v18i3.3533 | https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v18i3.3533

20) Da Silveira, C., Lages, C., & Simões, C. (2013). Reconceptualizing brand identity in a dynamic environment. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 28-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.020 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.020

21) De Chernatony, L. (2010). Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1-3), 157-179. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870432 | https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870432

22) Essamri, A., McKechnie, S., & Winklhofer, H. (2019). Co-creating corporate brand identity with online brand communities: A managerial perspective. Journal of Business Research, 96, 366-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.015 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.015

23) Evans, J., & Bridson, K. (2013). Branding the public art museum sector: a new competitive model. Asia Pacific Social Impact Leadership Centre.

24) Ferreira, J. (2012). Developing a museum brand to enhance awareness and secure financial stability. Tafter Journal. Retrieved 20 March 2022, from: https://www.tafterjournal.it/2012/07/02/developing-a-museum-brand-to-enhance-awareness-and-secure-financial-stability/

25) Ferreiro-Rosende, E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L., & Morere-Molinero, N. (2021). Artists brands and museums: understanding brand identity. Museum Management and Curatorship. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2021.1914143 | https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2021.1914143

26) García Valdés, M., & Suárez Marín, M. (2013). El método Delphi para la consulta a expertos en la investigación científica. Revista Cubana de Salud Pública, 39(2), 1-7.

27) Ghodeswar, B.M. (2008). Building brand identity in competitive markets: a conceptual model. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 17(1), 4-12. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420810856468 | https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420810856468

28) Gravari-Barbas, M. (2017). Arquitectura, museos, turismo: la guerra de las marcas. Revista de Arquitectura, 20(1), 102-114. https://doi.org/10.14718/revarq.2010.20.1.1573 | https://doi.org/10.14718/revarq.2010.20.1.1573

29) Iannone, F., & Izzo, F. (2017). Salvatore Ferragamo: An Italian heritage brand and its museum. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 13(2), 163-175. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-016-0053-3 | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-016-0053-3

30) Kabassi, K. (2017). Evaluating websites of museums: State of Art. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 24, 184-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.10.016 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.10.016

31) Kapferer, J.N. (1992). La marca, capital de la empresa. Deusto Editions.

32) Kist, C. (2020). Museums, challenging heritage and social media during COVID-19. Museum & Society, 18(3), 345-348. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v18i3.3539 | https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v18i3.3539

33) Landeta, J. (1999). El método Delphi. Ariel

34) Laursen, D., Kristiansen, E., & Drotner, K. (2016). The museum foyer as a transformative space of communication. Nordisk Museologi, 1, 69–88. https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3065 | https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3065

35) Lindsay, G. (2018). One icon, two audiences: how the Denver Art Museum used their new building to both brand the city and bolster civic pride. Journal of Urban Design, 23(2), 193-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2017.1399793 | https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2017.1399793

36) Mariutti, F., & Giraldin, J. M. (2014). Country Brand Identity: An Exploratory Study about the Brazil Brand with American Travel Agencies. Tourism Planning and Development, 11(1), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2013.839469 | https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2013.839469

37) Massi, M., & Harrison, P. (2009). The branding of arts and culture: an international comparison. Deakin business review, 2(1), 19-31.

38) Mindrut, S. Manolica, A., & Roman, C. T. (2015). Building Brands Identity. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 393 – 403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00088-X | https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00088-X

39) Minkiewicz, J., Evans, J., Bridson, K., & Mavondo, F. (2011). Corporate image in the leisure services sector. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(3), 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111129173 | https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111129173

40) Moorthi, Y.L.R. (2002). An approach to branding services. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(3), 259-274. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040210427236 | https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040210427236

41) Pencarelli, T., Conti, E., & Splendiani, S. (2017). The experiential offering system of museums: evidence from Italy. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 7(4), 430-448.

42) Pusa, S., & Uusitalo, L. (2014). Creating Brand Identity in Museums: A Case Study. International Journal of Arts Management, 17(1), 18-30.

43) Ramaswamy, V., & Ozcan, K. (2018). What is co-creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. Journal of Business Research, 84, 196-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.027 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.027

44) Recuero Virto, N., Blasco López, M.F., & San-Martín, S. (2017). How can European museums reach sustainability?, Tourism Review, 72(3), 303-318. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2017-0038 | https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2017-0038

45) Reguant-Alvarez, M., & Torrado-Fonseca, M. (2016). El método Delphi. REIRE, Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 9(1), 87-102. https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2016.9.1916 | https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2016.9.1916

46) Rentschler, R., & Gilmore, A. (2002). Changes in Museum Management. A Custodial or Marketing Emphasis?. Journal of Management Development, 21(10), 745–760. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710210448020 | https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710210448020

47) Samaroudi, M., Rodriguez, K., & Perry, L. (2020). Heritage in lockdown: digital provision of memory institutions in the UK and US of America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Museum Management and Curatorship, 35(4), 337-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1810483 | https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1810483

48) Scott, C. (2007). What Difference do Museums Make? Using Values in Sector Marketing and Branding. MPR-ICOM. Retrieved 20 March 2022, from: http://temp.icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/minisites/mpr/papers/2007-scotttxt.pdf

49) Stallabrass, J. (2014). The Branding of the Museum. Art History, 37(1), 148–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12060 | https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12060

50) Torres, I.M. (2017). A Territorial cohesion through cultural tourism: the case of the Umayyad Route. Methaodos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 5(1), 74-83. https://doi.org/10.17502/m.rcs.v5i1.140 | https://doi.org/10.17502/m.rcs.v5i1.140

51) Upshaw, L.B. (1995). Building Brand Identity. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

52) Urde, M. (2013). The corporate brand identity matrix. Journal of Brand Management, 20(9), 742-761. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2013.12 | https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2013.12

53) Vicente, E., Camarero, C., & Garrido, M.J. (2012). Insights into Innovation in European Museums. Public Management Review, 14(5), 649-679. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2011.642566 | https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2011.642566

54) Vivant, E. (2011). Who brands whom?: The role of local authorities in the branching of art museums. Town Planning Review, 82(1), 99-115. https://doi.org/10.2307/27975982 | https://doi.org/10.2307/27975982

55) Von Wallpach, S., Voyer, B., Kastanakis, M., & Mühlbacher, H. (2017). Co-creating stakeholder and brand identities: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Business Research, 70, 395-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.028 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.028

56) Wallace, M. (2016). Museum Branding. How to create and maintain image, loyalty and support. Rowman & Littlefield.

57) Ward, E., Yang, S., Romaniuk, J., & Beal, V. (2020). Building a unique brand identity: measuring the relative ownership potential of brand identity element types. Journal of Brand Management, 27, 393-407. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00187-6 | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00187-6

58) Zollinger, R. (2021). Being for Somebody: Museum Inclusion During COVID-19. Art Education, 74(4), 10-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2021.1905438 | https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2021.1905438

Notas

1) Due to the anonymity of the responses, the experts' comments will be quoted as E1 (expert number 1), E2 (expert number 2), etc.

Breve curriculum de los autores

Ferreiro-Rosende, Erica

Erica Ferreiro Rosende has a Master's degree in Tourism Products and Destinations Management from A Coruña University and a Master's degree in Education and Heritage from Murcia University. She has extensive experience in Picasso museums and their potential as a tourism resource. Her doctoral thesis deals with museum management, specifically museum brand identity